Tech in Plain Sight: Escalators [Hackaday]

If you are designing a building and need to move many people up or down, you probably will at least consider an escalator. In fact, if you visit most large airports these days, they even use a similar system to move people without changing their altitude. We aren’t sure why the name “slidewalk” never caught on, but they have a similar mechanism to an escalator. Like most things, we don’t think much about them until they don’t work. But they’ve been around a long time and are great examples of simple technology we use so often that it has become invisible.

Of course, there’s always the elevator. However, the elevator can only service one floor at a time, and everyone else has to wait. Plus, a broken elevator is useless, while a broken escalator is — for most failures — just stairs.

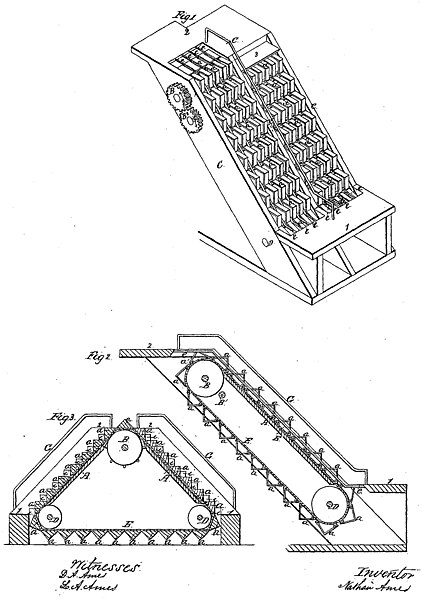

Early Concepts and Patents

The story of the escalator begins in the mid-19th century. In 1859, Nathan Ames, a patent attorney from Saugus, Massachusetts, patented the first known design of an “escalator,” though he never built a working model. His design, called the “revolving stairs,” was quite speculative. He suggested the device would be either manually powered or work with hydraulics.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that designs resembling modern escalators emerged. In 1889, Leamon Souder patented the “stairway,” which featured a series of linked steps. Like Ames, Souder never built a model of his invention. He’d later patent three other proto-escalator designs, including two shaped like a spiral.

By 1892, the patent office granted a patent to Jesse W. Reno’s “Endless Conveyor or Elevator.” A few months later, George A. Wheeler patented his design for a moving staircase, which was never built but influenced future developments. Charles Seeberger bought Wheeler’s patents and collaborated with the Otis Elevator Company to create a prototype that incorporated Wheeler’s ideas.

Jesse W. Reno created the first working escalator, which he termed an “inclined elevator.” In 1896, he installed it at Coney Island, New York City. This early version was essentially an inclined belt with cast-iron slats for traction. I moved along a 25-degree incline.

Charles Seeberger and Otis Elevator Company produced the first commercial escalator in 1899. This model won first prize at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. Unlike Reno’s design, which was also at the Exposition, Seeberger’s escalator had flat, moving stairs and a smooth step surface without the comb effect seen in modern escalators. Attendees of the exposition could also see escalators from the Link Belt Machinery Company, Piat, and Hallé.

Piat, a French firm, had installed a “stepless” escalator in Harrods back in 1898. It had a leather belt, and — reportedly — employees had to revive unnerved patrons who rode it with free smelling salts and cognac.

Several companies went on to develop their own escalator products, often under different names due to trademark rights held by Otis. For instance, the Peelle Company called their models the Motorstair, and Westinghouse referred to theirs as an Electric Stairway, while Haughton Elevator had the delightfully simple name of Moving Stairs. Otis lost their trademark in a 1950 case Haughton Elevator Co. v. Seeberger where the court confirmed that escalator had become a generic descriptive word.

Some old escalators, including the one at Macy’s Herald Square in New York City, still operate today. It opened in the 1920s but was retrofitted with metal steps in the 1990s. You can see it below from — not kidding– The Escalator Channel.

The Core Components

An escalator is essentially a continuously moving staircase powered by an electric motor. The main components include steps, tracks, handrails, and a drive system. Each of these plays a crucial role in the seamless operation of an escalator. The main structural component is called a truss and is typically a hollow structure that runs the length of the escalator and supports the straight sections of the track.

The tracks guide the movement of the steps. There are two sets: one for guiding the steps up and another for guiding them back down. This creates a continuous loop that the steps ride.

Steps are the most visible part of the machine and are usually made from a single piece of die-cast aluminum or steel. They are linked together like a chain and mounted on tracks. Each step has wheels on the underside that roll along these tracks, allowing the steps to remain level while moving along the inclined path.

The handrails (part of the sides known as the balustrade) move in sync with the steps because the pulleys that drive them are on the same motor. The steps emerge from and disappear under the landing platforms at each end. The landing platforms have a comb to stop large things from entering the machinery. Many escalators also have a sensor, so if something unexpected enters the comb, the escalator will stop.

All About the Movement

Of course, the heart of it all is the motor. It is often under the top landing platform along with the drive gear. Another gear that reverses the direction of the steps.

The magic of an escalator’s movement lies in its looped system of steps. One track guides the two wheels in the front of the step that form a drive chain, and another guides the two back wheels. By controlling the vertical distance between the tracks, the steps can be made to lie flat or stand up.

If it doesn’t make sense, check out the animation from [Jared Owen] below.

The Future

It doesn’t seem like the escalator is going anywhere soon. However, there are always developments to make them safer, more efficient, and faster. Of course, today’s escalator will have much more control and monitoring via the network than the Macy’s building engineer could have dreamed of. Some escalators can now control their speed depending on the size of the crowd or even stop when no one is using them.

Want to really understand what’s inside? Why not print a model? Or, go to the woodshop and build a torture device for your Slinky.

Featured image: “Escalators 1” by Eric Pesik

![tech-in-plain-sight:-escalators-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/165185-tech-in-plain-sight-escalators-hackaday.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)