What’s a Transfluxor? [Hackaday]

In the 1967 movie The Graduate, a wise older man gives some advice to the title character: plastics. Indeed, plastics would become big business. In 1962, though, a computer-savvy character might have offered a different word: transfluxor. What’s a transfluxor? Well, according to computer history sleuth [Ken Shirriff], it was the heart of a 20-pound transistor computer from Arma. Of course, plastics turned out to be a better bet, but in 1962, the transfluxor seemed to be the wave of the future.

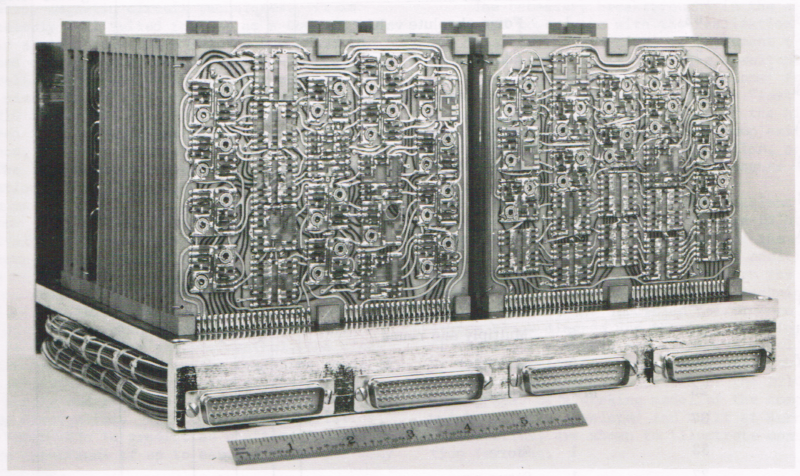

In 1962, most computers were room-sized, but the Arma was “micro” taking up just 0.4 cubic feet — less than an Apple II. It would eventually spawn computers used in ships at sea and airplanes ranging from the Concorde to Air Force One.

The computer was a bit odd since it had a 22-bit word, and it processed them one bit at a time. Serial computers like this were relatively common in the early days of computers because it dramatically reduced the gate count — important when trying to cram transistors into a tiny box. Of course, the serial data path meant the 1 MHz clock was quite slow. The machine only did about 36,000 instructions per second. While it only had 19 instructions, some of them were more powerful than many computers of the day. For example, the machine could multiply, divide, and even do square roots.

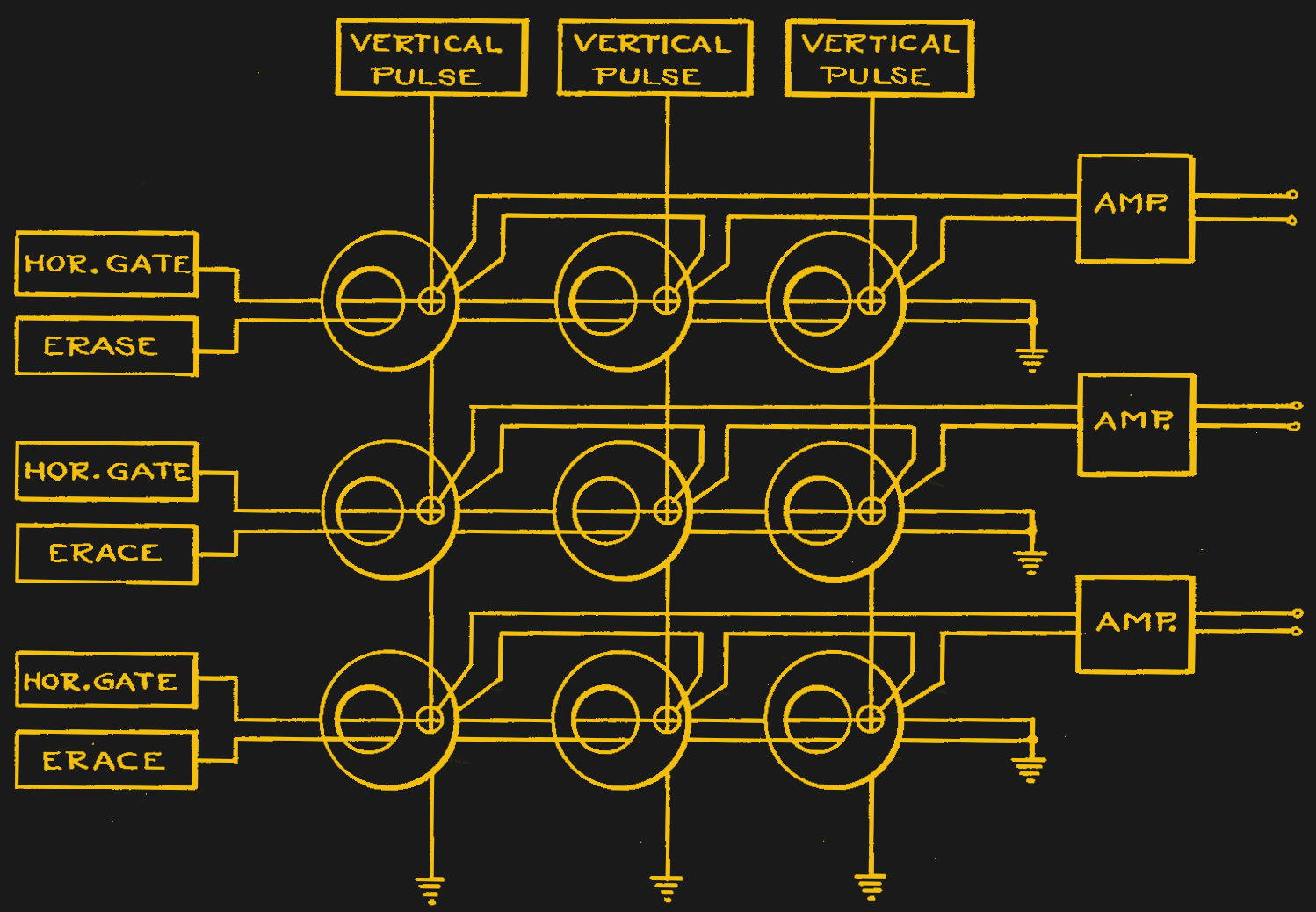

So what’s a transfluxor? You can read [Ken’s] post, but essentially it was a special type of core memory. Normal cores are like a donut. A transfluxor core is like a donut with a big off-center hole and a smaller hole near one edge. You write to the core through the big hole and read through the small hole. Along with some extra circuitry, this allowed the core to be read without destroying the stored data.

There’s a lot more information about this computer, the company behind it, and the later versions of it in the original post. We always enjoy [Ken’s] musing, which ranges from inside ICs to more conventional core memory.

![what’s-a-transfluxor?-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/171418-whats-a-transfluxor-hackaday.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)