Vulcan Nails First Flight, but Peregrine Falls Short [Hackaday]

For those with an interest in the history of spaceflight, January 8th promised to be a pretty exciting day. Those who tuned into the early morning live stream were looking forward to seeing the first flight of the Vulcan Centaur, a completely new heavy-lift booster developed by United Launch Alliance. But as noteworthy as the inaugural mission of a rocket might be under normal circumstances, this one was particularly special as it was carrying Peregrine — set to be the first American spacecraft to set down on the lunar surface since the end of the Apollo program in 1972.

Experience has taught us that spaceflight is hard, and first attempts at it doubly so. The likelihood of both vehicles performing as expected and accomplishing all of their mission goals was fairly remote to begin with, but you’ve got to start somewhere. Even in the event of a complete failure, valuable data is collected and real-world experience is gained.

Now, more than 24 hours later, we’re starting to get that data back and finding out what did and didn’t work. There’s been some disappointment for sure, but when everything is said and done, the needle definitely moved in the right direction.

Vulcan: Better Late than Never

Since their formation in 2006, United Launch Alliance (ULA) has maintained a 100% mission success rate between their primary rockets, the Atlas V and Delta IV. While there were always cheaper rides to space, notably on Russia’s Soyuz rocket, ULA became known as the launch provider you selected if you absolutely had to get your payload into space.

But by the early 2010s, it was clear the commercial launch market was changing. Not only was it far cheaper to fly on the Falcon 9, but SpaceX was launching them at (when compared to the entrenched players) a startling rate. While their legacy rockets still had the edge in reliability, guaranteeing ULA certain high-profile payloads, it was clear they needed to develop a cheaper and more agile rocket to remain competitive.

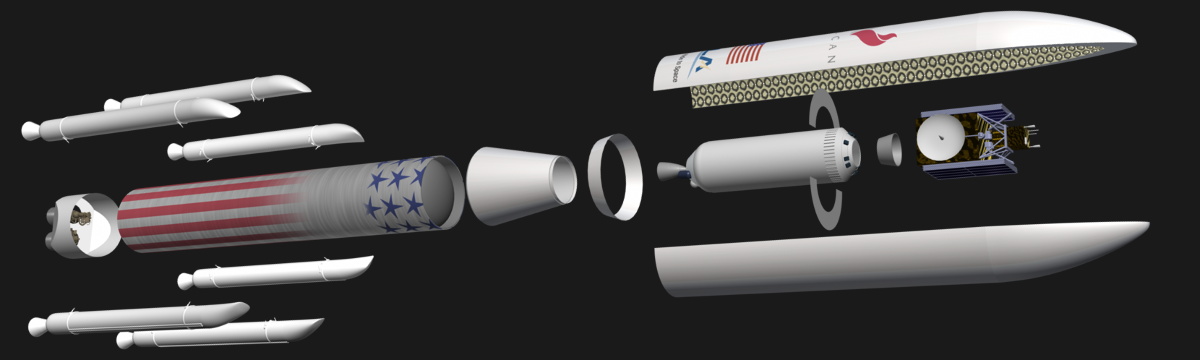

In addition, the continued use of the Russian RD-180 rocket engines that powered the Atlas V were becoming a political liability. So in 2014, the decision was made to take all the knowledge and experience gained while operating the Atlas and Delta and combine that into a new booster: Vulcan Centaur.

It was hoped that the rocket, a combination of the all-new Vulcan first stage and an evolved version of ULA’s Centaur III second stage, could be flying as soon as 2019. But the program suffered several delays due to the slower than expected development of its BE-4 engines by Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Plans to make the system partially reusable, similar to SpaceX’s Falcon 9, were also delayed indefinitely in order to get the program operational sooner.

While an explosion during the testing of the Centaur upper stage in March of 2023 did push the date of the rocket’s inaugural flight out to 2024, the January 8th launch apparently went off without a hitch — an even more impressive feat when you consider that the BE-4 engines are powered by liquid methane and liquid oxygen, a combination colloquially known as methalox, which had never successfully been used by an American orbital rocket previously. Other methalox vehicles from the US, such as SpaceX’s Starship or the Relativity Space Terran 1, have flown but have failed to achieve orbit.

In a post to social media, CEO of United Launch Alliance Tory Bruno said that Monday’s launch was among the smoothest he’d ever seen in his career. While obviously not the most unbiased source in this case, it’s clear that it was a day worth celebrating at ULA.

Peregrine: A Dramatic Stumble

While the first flight of the Vulcan Centaur looks to have been the picture of success, Peregrine’s inauspicious start was arguably the polar opposite. Just hours after the lander separated from the Centaur upper stage, it was clear something had gone terribly wrong, and that its historic return to the Moon was likely out of reach.

Among the cargo being brought to the Moon, Peregrine was carrying more than a dozen memorials and time capsules, eight scientific instruments, the Iris rover from Carnegie Mellon University, and five small autonomous robots built by the Mexican Space Agency.

According to Astrobotic, it seemed the mission was off to a solid start when Peregrine first separated from the booster. Teams on the ground established communications with the rover, and critical systems started to come online as expected. But shortly after enabling its propulsion systems, the craft seemed unable to maintain the necessary attitude to keep its solar panels pointed to the sun. This in turn lead to the vehicle’s batteries being drained to a dangerously low level within just a few hours.

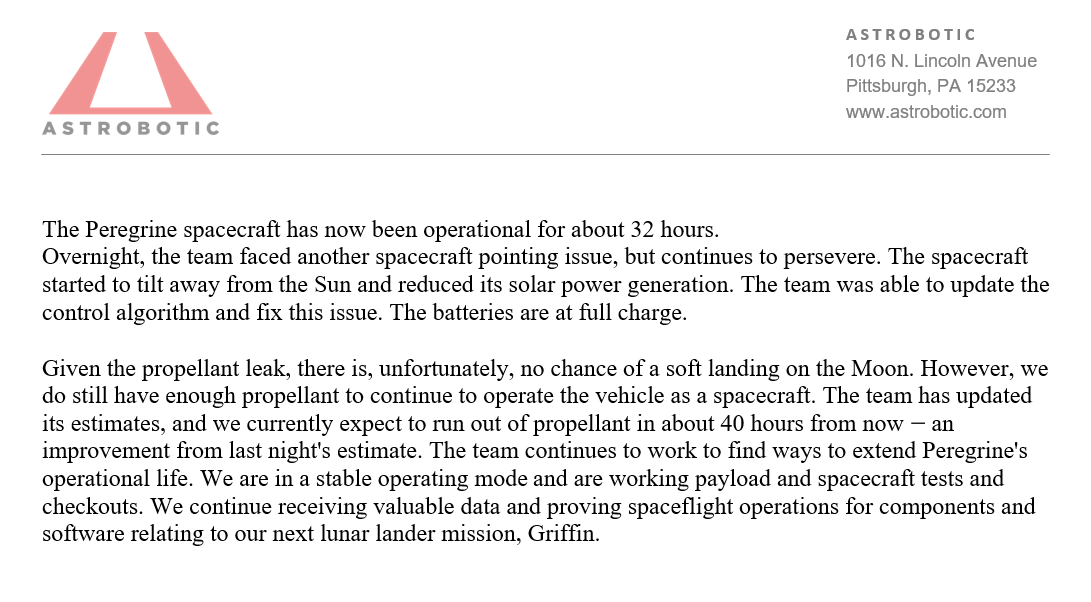

Approximately ten hours after launch, Astrobotic posted an update to social media announcing that they had stabilized the craft and that its batteries were now charging. Unfortunately, while the immediate situation had improved, the concern on the ground was that the craft’s propulsion system had suffered some sort of failure. In a subsequent post, they confirmed the worst case scenario: that a leak was not only destabilizing the craft, but bleeding it of the propellants it needed to make a landing on the Moon.

As of the last update from Astrobotic, a landing had been completely ruled out. Further, between the leak and the constant maneuvering thruster firings necessary to keep the craft properly oriented, the team estimates the tanks will be dry within 40 hours. Before then the team will attempt to set it on a trajectory that will take it as close as possible to the Moon, but without the ability to orient itself, there’s no guarantee on how long communications with the craft will hold out.

Space is Still Hard

All told, January 8th will certainly be looked back on as a major day for spaceflight. America put its first methalox rocket into orbit, and just hours later, had its lunar landing aspirations dashed. Although modern technology has greatly improved our overall access to space, its days like this that remind us of how easily things can go sideways.

But that doesn’t mean we’ll stop trying. The Moon is still calling, and we won’t have to wait long until another mission is on its way to our nearest celestial neighbor. The Nova-C lander, built by Intuitive Machines and also funded by NASA’s CLPS program, is due to liftoff in February. No matter what happens, we’re eager to see it unfold.

![vulcan-nails-first-flight,-but-peregrine-falls-short-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/161723-vulcan-nails-first-flight-but-peregrine-falls-short-hackaday.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)