The Hunt For Alien Radio Signals Began Sooner Than You Think [Hackaday]

Every 26 months, Earth and Mars come tantalizingly close by virtue of their relative orbits. The closest they’ve been in recent memory was a mere 55.7 million kilometers, a proximity not seen in 60,000 years when it happened in 2003.

However, we’ve been playing close attention to Mars for longer than that. All the way back in 1924, astronomers and scientists were contemplating another close fly by from the red planet. With radio then being the hot new technology on the block, the question was raised—should we be listening for transmissions from fellows over on Mars?

I Got Too Excited When I Thought You Were Around

Flashback to 1924, a time when the cosmos was less understood but no less marveled at. Earth and Mars were drawing near, and with that, an ambitious, albeit quaint by today’s standards, attempt to probe the Red Planet for signs of life was set into motion. It wasn’t with the sophisticated rovers or orbiters of the modern era. Instead, the plan was to keep out a listening ear for potential Martian radio broadcasts.

The backdrop to this interplanetary eavesdropping was a world captivated by the possibilities that have all but been dashed today. It’s funny to think, but 100 years ago, astronomers and scientists knew much less about the solar system. The idea that Mars was not just another speck in the sky but a world teeming with life, perhaps even civilizations, was still a somewhat viable one.

By 1924, theories of canals on Mars and potential intelligent life were on the books. They weren’t necessarily widely believed, but they were a topic of scientific discussion in recent decades that hadn’t outright been disproved. Increasing knowledge of the planets was beginning to suggest to scientists that our neighbouring rocks might be uninhabitable, but the matter wasn’t by any means settled.

Despite the growing skepticism within the scientific community, the hope of contacting Martian life lingered. So, in 1924, as Earth and Mars drew close like cosmic neighbors leaning over a fence, the U.S. orchestrated a grand gesture, just on a chance—National Radio Silence Day.

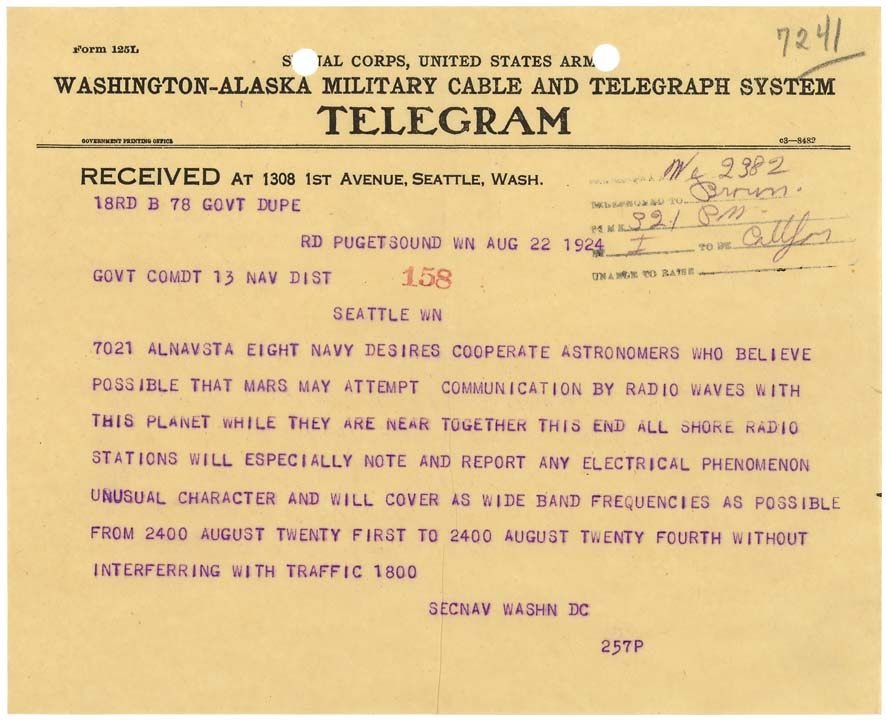

The idea was that terrestrial radio transmissions should be hushed as much as possible such that any Martian transmissions might better be heard by radio operators. Citizens were urged to quiet their radio transmissions for the first five minutes of every hour. US naval stations were instructed to lend Earth’s ears to the cosmos, noting and reporting “any electrical phenomenon” of unusual character across “as wide band frequencies as possible.” This was all in the hope that someone, somewhere might hear a faint howdy or hello from a Martian. It was a moment of wide-eyed optimism. The hope was to hear a crackle from a speaker. Some distant sound that told us somebody else was out there.

The day was actually promoted as a 36-hour long period from August 21 to August 23. The United States Naval Observatory went as far as using a small airship to raise a radio receiver 3 kilometers miles into the air for better reception. A Professor David Peck Todd had been charged with clearing the airwaves, and persuaded the Army and Navy to log observations over the three-day period. He was allegedly less successful in convincing private broadcasters, who were reluctant to wind back operations for so long.

Alas, with ears turned to the sky, the cosmos remained silent. Either the people of Mars were too busy to contact us, or they didn’t want to make new friends. Or, as we assume today, there were simply no Martians to begin with. No Martian dispatches were received, and Earth was left to ponder the silence.

It’s easy to look back and think about what a long shot it really was. A bunch of low-tech receivers hoping to pick something up on relatively low-frequency bands, listening out for a transmission from a planet drier than an Appalachian summer. But that’s all with the benefit of hindsight. If you were back in 1924, and knew what they knew back then, could you have resisted firing up your receiver for a listen?

The Modern Age

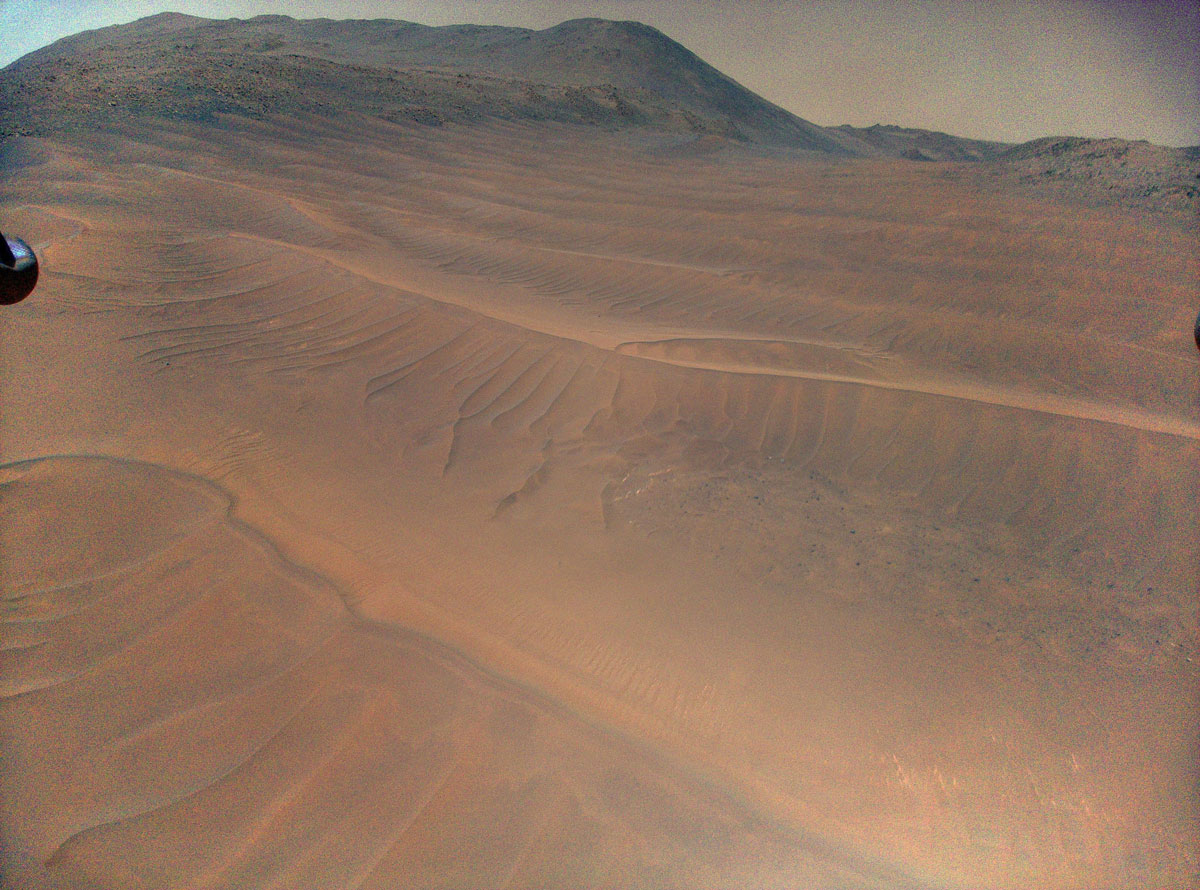

Today, we understand much more about the harsh realities of Mars, its barren landscapes, and thin atmosphere offering scant hospitality for life as we know it. We’re pretty certain nobody’s kicking around over there, and we’re not listening out for their Top 40 stations or diplomatic calls to establish relations with Earth.

And yet the search for extraterrestrial intelligence goes on. It’s so much more sophisticated now, with scientists hunting for emissions in different frequencies and aiming radio telescopes into patches of sky we think most likely might harbor some new friends. By the 1990s, systems like the Billion-channel Extraterrestrial Array (BETA) were monitoring hundreds of millions of radio channels at once with multiple antennas automatically investigating any candidate signals captured for further investigation. After the letdown of the Wow! Signal, scientists adapted new techniques to better capture potential signals from space and rule out those that came from Earth. We’ve even made our own transmissions in an attempt to reach out directly to other species.

As of yet, we’re yet to find definitive evidence that anyone else is in this big old universe with us. Some find that a comfort, while others find it lonely. At its heart, humanity is a social species. One that has always dreamed and wondered about who might be living on the other side of those mountains on the horizon. We’ve had that answer to that question for a long time now. As for who lies beyond the neighbourhood of our star system? We’ll be watching and wondering for some time yet.

![the-hunt-for-alien-radio-signals-began-sooner-than-you-think-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/174405-the-hunt-for-alien-radio-signals-began-sooner-than-you-think-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)