The Cockpit Voice Recorder Controversy [Hackaday]

Every time there’s a plane crash or other aviation safety incident, we often hear talk of the famous “black box”. Of course, anyone these days will tell you that they’re not black, but orange, for visibility’s sake. Plus, there’s often not one black box, but two! There’s a Flight Data Recorder (FDR), charged with recording aircraft telemetry, and a Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), designed to record what’s going on in the cabin.

It sounds straightforward enough, but the cockpit voice recorder has actually become the subject of some controversy in recent times. Let’s talk about the basics of these important safety devices, and why they’re the subject of some debate at the present time.

That’s a Hot Mic

When it comes to figuring out what happened in an air disaster, context is everything. Flight data recorders can tell investigators all about what the plane’s various systems are doing, while more advanced maintenance recorders developed by airline manufacturers can deliver even more granular data. Knowing the control inputs from the pilots, the positions of control surfaces, and system statuses is all relevant to piecing together what happened. However, there’s also a lot that can be learned from the pilots themselves. Past research has found pilot error to be a factor in over a third of major airline crashes. Knowing what pilots are thinking at a given moment isn’t quite possible, but having a recording of their conversation can provide good insight. The cockpit voice recorder plays a pivotal role in this regard. It’s also useful for capturing other sounds, too, like rattles, thuds, explosions, or alarms going off in the cockpit.

This information can prove crucial in the event of an incident or accident. It aids investigators who must try and piece together a sequence of events and contributing factors. An instructional example is the case of Air France Flight 447. Flight data indicated that the plane was likely subject to icing on the pitot tubes, leading to unreliable airspeed measurements. The crew’s response was incorrect for the given situation, with the voice recording clearly laying out how the errors made led to the tragic loss of the aircraft and the lives of all on board. Without the voice recording, there would have been a far greater mystery around how the plane came to enter its deadly stall before plummeting into the water.

So, cockpit voice recorders are super useful. With today’s modern storage technologies, we must be recording and storing what goes on in every flight, right? No? Well… surely we’re recording for the full length of every flight, at least. Again, not quite.

As it stands today, there are notable differences in regulations around the world regarding the length of recording time required for a CVR. Once upon a time, recording durations were as short as 30 minutes, but this was often found to be insufficient to gain a good understanding of a safety-related incident. Today, in the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration mandates that planes fitted with cockpit voice recorders have a recording duration for a minimum of two hours. Recording is done on a loop, such that as the recording continues, older audio is overwritten, preserving just the last two hours of sound recorded from the cabin.

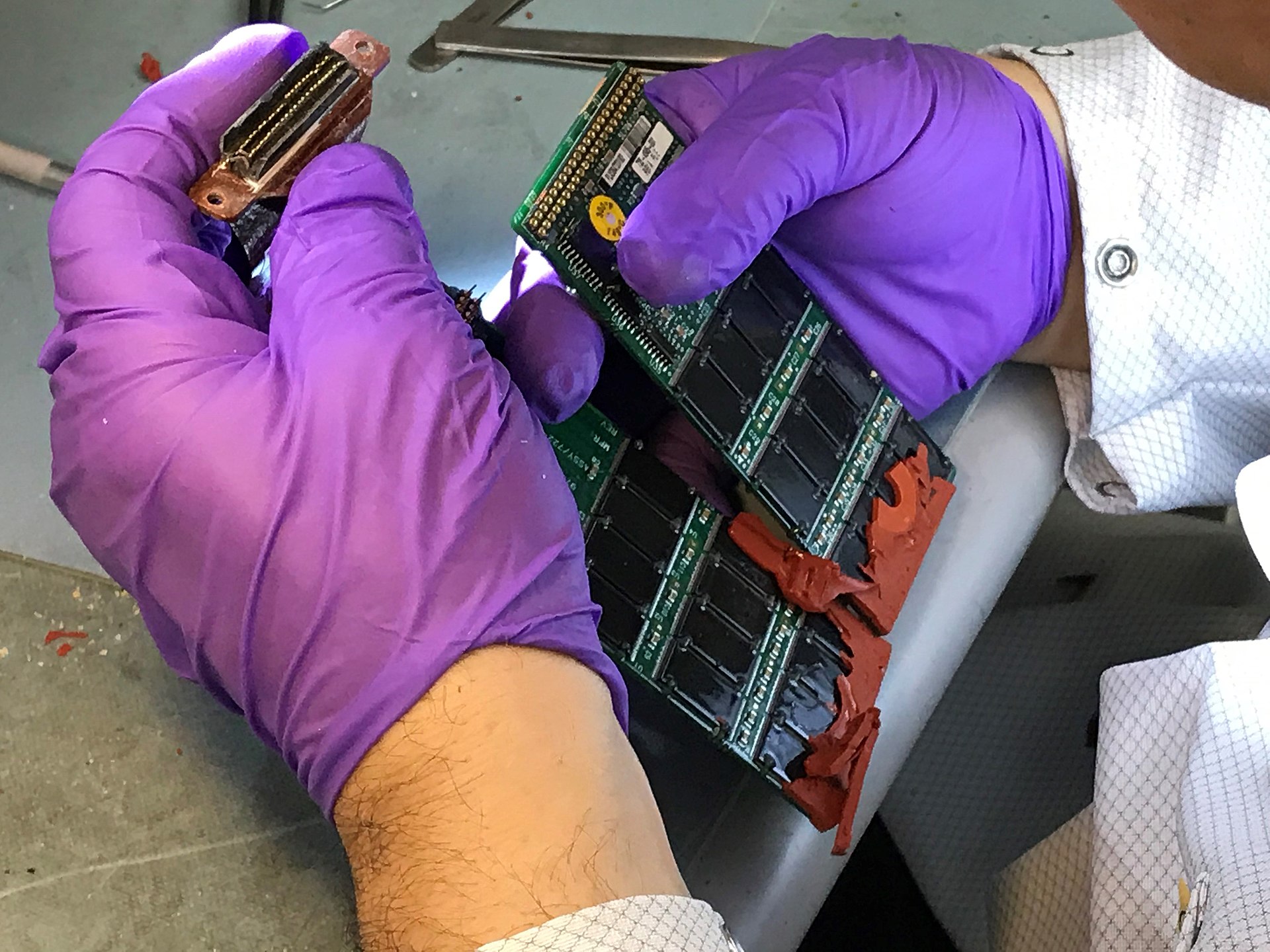

Obviously, modern technology has made storage incredibly cheap. While early units often used magnetic recording on wire or tape, more recent designs have relied on solid state digital recordings. There’s no real technical reason for CVRs to only record two hours of audio, but airlines and aircraft manufacturers build to the regulation. There’s also great expense required to get a new piece of equipment designed and approved for safety-critical use in an aircraft. Without a regulation mandating longer recording times, US airlines have little reason to invest in upgrades to their fleets.

In Europe, however, there’s a rather different picture. Under the regulations set by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), aircraft with a maximum takeoff weight exceeding 59,500 pounds must have cockpit voice recorders that store at least 25 hours of audio. This regulation applies to aircraft manufactured after Jan 1, 2021, and doesn’t explicitly require that earlier aircraft be retrofitted.

The European move has led to calls for the FAA to adopt similar minimum standards. Most recently, the chair of the National Transport Safety Board has called for the 25-hour recording period to apply not just to newly built aircraft, but existing planes as well. This was in part due to the case of Alaska Airlines Flight 1282, in which a Boeing 737 MAX 9 had a door plug blow out at altitude. Unfortunately, after the plane landed safely, neither the crew nor other technicians switched off the breaker for the cockpit voice recorder. Thus, it kept recording while on the ground, and overwrote the relevant period in short order. A 25-hour recording would have provided a much longer period for somebody to realize and shut off the CVR, even if it’s an imperfect solution. The 25-hour limit is also of use to provide full coverage of longer international flights. The FAA continues to accept comment on the matter until February 2, 2024.

Privacy in the Cockpit

There are other limits on cockpit voice recorders, too. Privacy has been a major concern for pilots and aviation unions over the years, primarily regarding the potential misuse of recordings. While many of us are recorded by surveillance cameras on a daily basis in our places of work, they seldom capture the intimate details of conversations between colleagues. Pilots, on the other hand, have every word they speak recorded by multiple microphones in the cabin. On long flights, pilots will typically have all sorts of personal conversations, just like anyone else at work. There’s naturally some apprehension about having one’s conversations stored, and possibly listened to, in such a manner.

By and large, recordings from cockpit voice recorders are not released publicly, even in the event of a major crash investigation. Instead, when the NTSB investigates an incident, it forms a committee to listen to a recording. This committee usually consists representatives from the NTSB and FAA, the aircraft manufacturer, and members of the pilots union. The committee then produces a transcript for further use in the investigation and public distribution, where necessary.

While transparency can aid public understanding and trust in aviation safety processes, there are concerns about sensationalism and misinterpretation of the technical conversations by the general public. These matters are treated with the highest sensitivity; Congress mandates that CVR audio is not released to the public, in whole or in part. Even the written transcript can only be released on a set timetable, typically at a public hearing or when a report is issued for public consumption.

While there are strict rules in place, pilot unions and individuals have come out against CVR reforms on the table in the US. Prime concerns remain around privacy, and fears that airlines might begin to use cockpit recordings to pursue disciplinary actions or surveil pilots, rather than sticking to using the systems for safety investigations. Others contend that, in some cases, pilots have even worked around existing 2-hour recording limits to cover their tracks in cases of potential misconduct.

Ultimately, controversy continues to hold back cockpit voice recorders from being as good as they possibly could be. It’s likely that crash investigators in future will have to make do with what they can get as opposition to more capable recorders remains potent in the US. Meanwhile, European regulators seem happy to charge ahead and enforce a greater standard. We may yet learn from this folly, but hopefully not through the loss of some critical information that could solve a future airline tragedy.