Share Your Projects: Take Pictures [Hackaday]

Information is diesel for a hacker’s engine, and it’s fascinating how much can happen when you share what you’re working on. It could be a pretty simple journey – say, you record a video showing you fixing your broken headphones, highlighting a particular trick that works well for you. Someone will see it as an entire collection of information – “if my headphones are broken, the process of fixing them looks like this, and these are the tools I might need”. For a newcomer, you might be leading them to an eye-opening discovery – “if my headphones are broken, it is possible to fix them”.

There’s a few hundred different ways that different hackers use for project information sharing – and my bet is that talking through them will help everyone involved share better and easier. Let’s start talking about pictures – perhaps, the most powerful tool in a hacker’s arsenal. I’ll tell you about all the picture-taking hacks and guidelines I’ve found, go into subjects like picture habits and simple tricks, and even tell you what makes Hackaday writers swoon!

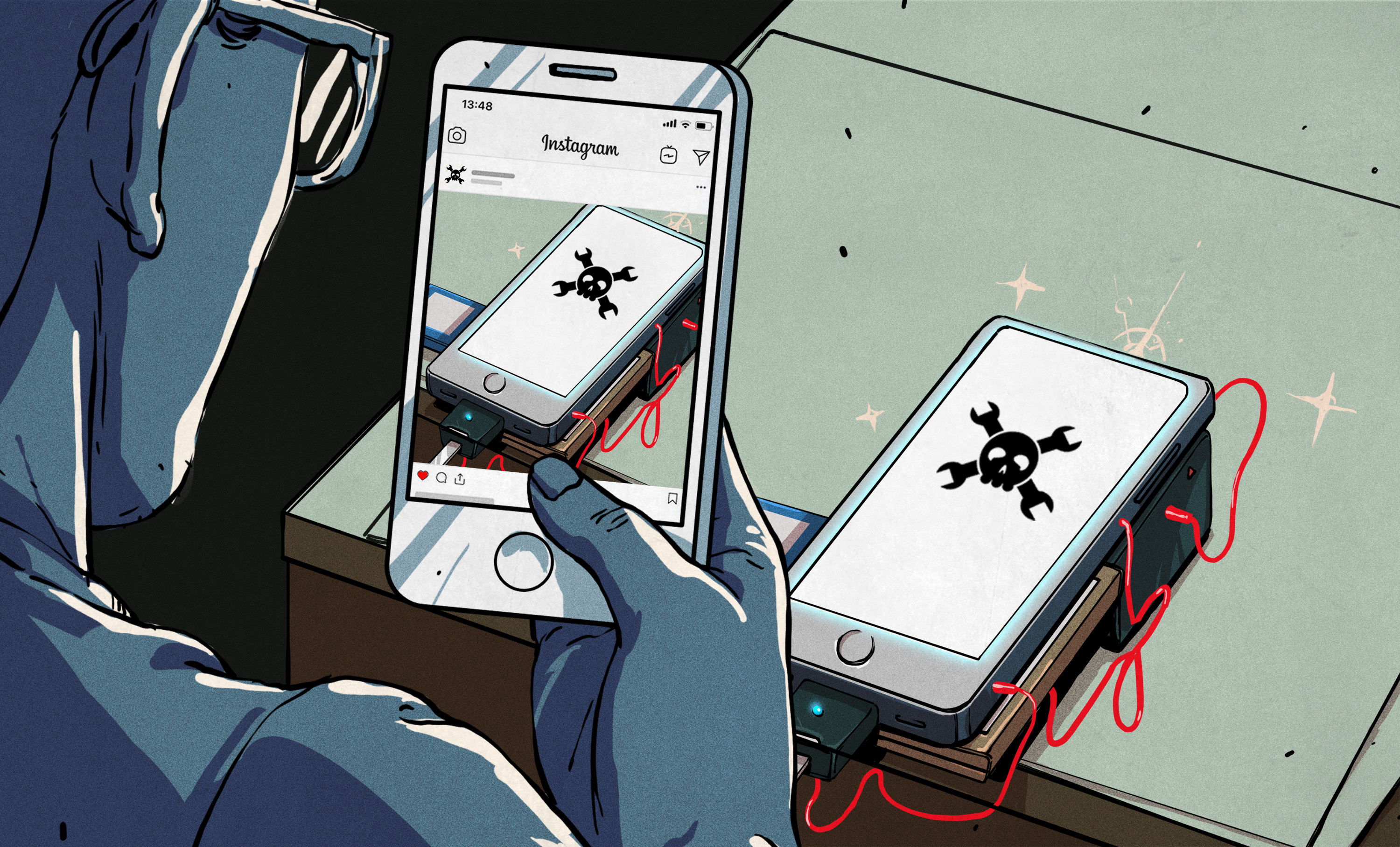

To start with, here’s a picture of someone hotwiring a car. This one picture conveys an entire story, and a strong one.

Thanks to our natural curiosity, it also immediately raises questions. Part of these questions, you can immediately figure out answers to – they’d be half-rhetorical prompts your mind makes up.

“So… You can jumpstart a car by just touching wires together? Is that just how simple car startup is, on a fundamental level – two wires being shorted together? Should it be any more complicated? And if it’s that simple, how did we secure our cars so that they aren’t hijacked more? Are “start engine” buttons just key mechanisms, repackaged? If it’s gonna cost me $200 to duplicate my car key, could it be easier to buy a new car lock mechanism with a set of keys instead and replace the entire mechanism?”

If you’ve never seen hotwiring, you’re now familiar it thanks to this picture alone. To hotwire a car, you tear out the key slot, then jumper a few of the wires. Now, that’s a seriously old car – in real life, hijacking a car hasn’t been this simple for a long time. There’s tools like the immobilizers, tied into the ECU on a deeper level than two wires; before those, we’ve had a vivid market for remote car alarm mechanisms of various kinds, some more vulnerable than others. Nevertheless, just like many other examples of the physical and cyber- security world, it remains a punchy demonstration of exploiting a weakness, with everything you need to grasp it being conveyed in a single picture.

Flipping Bits

A picture is in a unique position to light up someone else’s neurons. What’s more, pictures do this with unparalleled efficiency. I remember how, in my childhood, I’ve seen such a photo in a book about inventions, describing hotwiring in some context I no longer remember – which helped me go from “cars work, but I don’t quite know how” to “cars are electromechanical creations, and this is how I can map fundamental principles of other areas onto them”. In my own small theory of learning, which I keep in my head, I call such events “bitmasks” – it’s something you create, that interacts with someone else’s brain and creates a new pathway, as if enabling a new brain peripheral which lets us interact with our world in a unique way.

Pictures are a highly effective kind of bitmask in online world – by now, entire platforms are tailored towards pictures, and on Hackaday too, article has to have a picture with it no matter what. For the offline world, the most effective bitmask is hacker-friendly hardware – just remember an entire generation of hackers raised on 8-bit computers and game consoles. This line of thinking might feel grim as you realize that nowadays, generations are being raised with smartphones, hacker-hostile in many important ways – on the other hand, nowadays we have laptops, single-board computers, and devboards aplenty.

In fact, there’s a low-effort and high-impact way to share your projects by heavily relying on pictures, as long as you’re diligent about snapping a picture every now and then. Once you have a series of photos or pictures that convey your project’s story, post them as an Imgur gallery or Twitter thread, with a caption under each photo that gives the context and any missing detail. A layer or two of your project will be lost in such a way, and you’ll really want to open-source your project where appropriate, negating the loss from the other end. It also doesn’t work for all projects – software projects and certain hardware projects won’t be described as well by a photo gallery. However, this is still an incredibly efficient way of information delivery.

Take All The Pictures

Now, we’ve figured it out, a single picture can be enormously powerful – if well-timed pictures can lead to international scandals, then one of your pictures could no doubt, one day, be instrumental as part of the overall hacker movement. Of course, on average, it’s way more likely that your pictures will make other hackers think, smile, or dream. You might not know which pictures does it, however – you’ll want to learn to take them often, and at just the right moments.

A good way to create a picture-taking habit is to have someone wait for your results. If there’s an audience waiting for you as you hack, you will naturally try to share your project’s crucial moments with them, and take pictures in a way that an outside audience could appreciate, too. It could be a Twitter thread you create as you go through a project, DMs with your friend passionate about some topic, or a Discord channel where folks interested in the same topic hang out.

For instance, take Discord – it is normally a bad platform for publicly presenting your projects, as it’s a fleeting medium and it’s not searchable – plus, you can’t quite give your friend a thread link if they’re not in the server, and here on Hackaday, we can’t feature a Discord thread either! However, if you’re in a Discord server where a few friends are waiting for you as you hack on something, every time you reach a small milestone, there will be a thought on your mind: “Hold on, others will want to see what I see right now!” Discord will also preserve your pictures indefinitely, so if you ever want to make your project public, you can simply go back in channel history, download the pictures, copy-paste the messages and go the Imgur/Twitter thread route.

Another way is creating a Twitter or Mastodon thread, documenting a project as you go. That’s what a microblog is for, after all. In the same way, this helps you develop a habit of taking pictures when it matters, both reminding you that you need to take a picture every so often, and developing a judgment on when it’s best to do so. With Twitter, the pictures instantly go online to an arbitrarily wide audience, and while Twitter searchability is subpar compared to blogs, it’s still better than a Discord channel, which are closed by default unless a lot of effort is applied.

Take Them Well

Of course, it matters how you take pictures. A picture represents a short story, in a way, so it very much matters that you have all the important parts of the story in shot and visible, and the less-than-important parts stay out. On the bright side – most often, you only need a smartphone to take your pictures, and that’s something you likely already have.

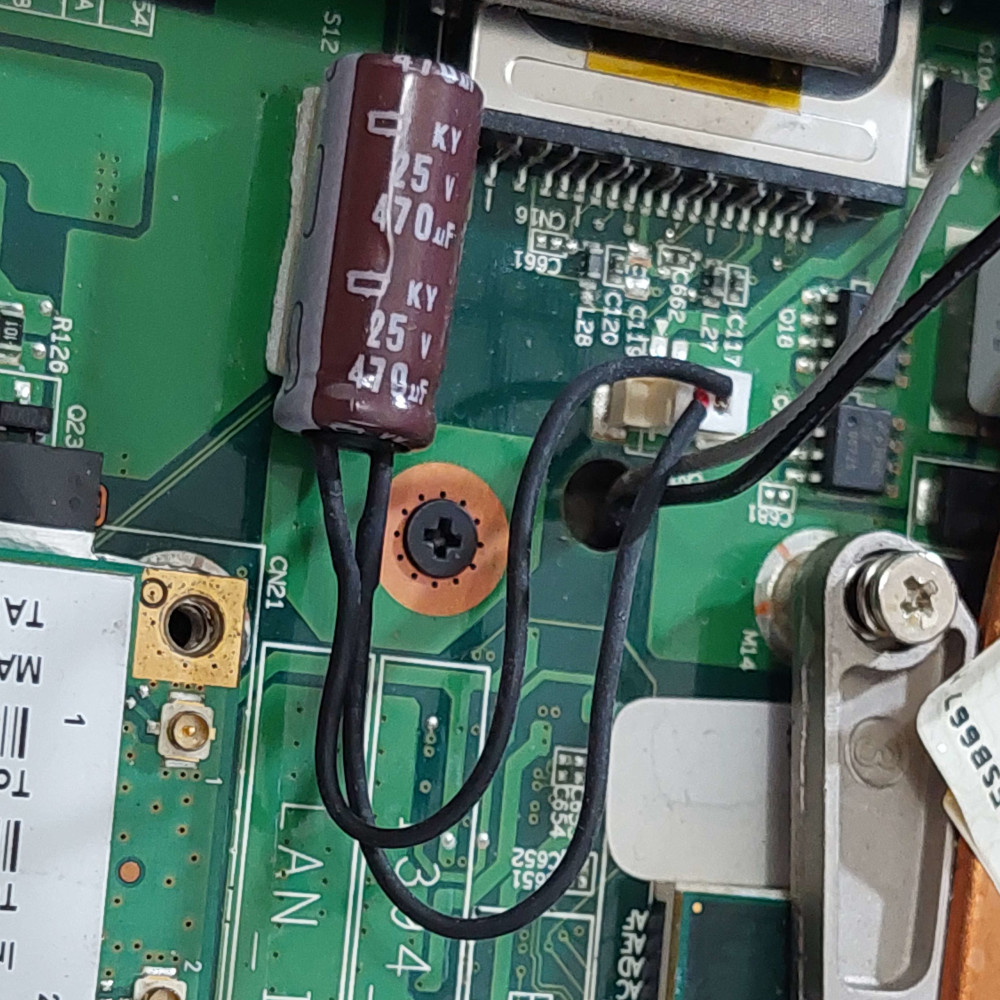

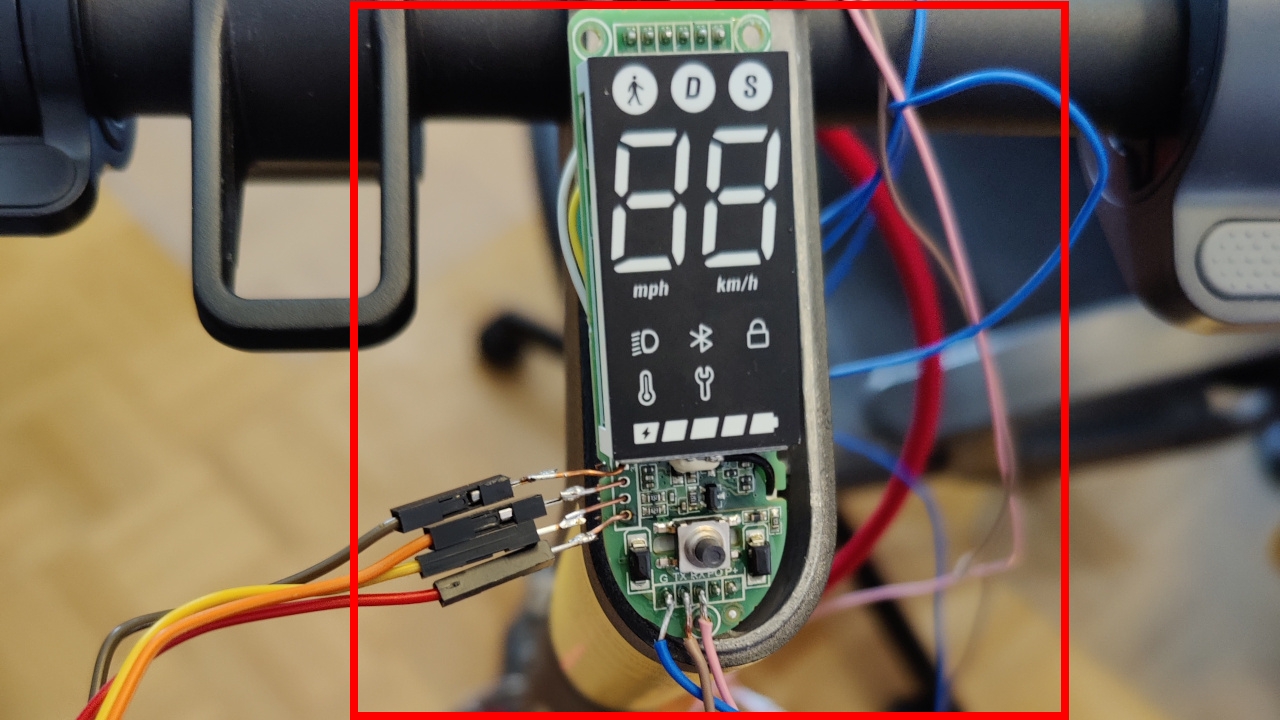

Lighting is perhaps the most important requirement. Say, you’re taking a picture of your PCB in action, with wires attached – a great kind of picture for conveying what you’re hacking on! You need to figure out a way to minimize both shadow and glare in the shot. Depending on how your hacking surface looks, there might be a suitable amount of light for this, or nowhere near enough – you’ll likely move the camera around for a bit as you figure it out.

It helps if you have some light sources at your control. Not all pictures need them – if you’re taking an in-progress picture of your workbench, it’s likely decently well-lit. On the other hand, if you need to take a closeup of a PCB and how things are wired up to it, you’ll want to have an extra light source handy and under your granular control – at my desk, I use a lamp with a bendy neck that I can move around, and in a pinch I use the flashlight function of my second smartphone.

Another important part is the background – for instance, in products, people typically try and go for clean-white. It’s doable – hackers have built light boxes for taking clean-white-background pictures before, and they’re wonderful for when you want things to be perfect. In a pinch, I’ve used a sheet of paper to compromise – and I’ve also learned that it’s not always you need a clean white background for a product picture that sells.

Say, you use a smartphone for your pictures, and you’re trying to do a close up picture of a chip on some PCB. Depending on how fancy it is, you might find that, no matter how close up you move the smartphone, it won’t focus. In this case, it might be actually beneficial to move it away a bit – many smartphones can’t focus too close up, but will happily give you a sharp picture from far away; even if you end up having the entire PCB in the shot, you can always cut it up!

And Bring Them To Us

Here’s a secret if you’re looking to have your project covered on Hackaday! We try to pick a picture that represents your project and also attracts readers to the article. For every article, we need two pictures – one 16:9 for the article page, and one 1:1 for sidebar and social media thumbnail. This means that, while a portrait (vertical) picture might very much work for your project page, it’s more than likely subpar for Hackaday purposes.

If you have more than one picture of the hardware, make sure to add them somewhere we can download them, and in quality better than the one you embed! For instance, having small pictures alongside your GitHub-published writeup is cool, but when we can only download a 400 x 400 thumbnail version of the pic, we can’t really use it.

All in all, having pictures is a huge boost for bringing your project’s essence to others’ attention, a strong amplifier for whatever you’re hacking on. Next time, let’s talk about how we share our projects when it comes to PCBs we create!

![share-your-projects:-take-pictures-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/118045-share-your-projects-take-pictures-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)