Retrotechtacular: The Nuclear Cruise Ship of the Future Earns Glowing Reviews [Hackaday]

The average modern cruise ship takes about 250 tons or 80,000 gallons of fuel daily. But can you imagine a cruise ship capable of circling the globe fourteen times before it needed to top off? That was the claim for the NS Savannah, a nuclear-powered cruise ship born out of President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative.

The ship was a joint project of several government agencies, including the US Maritime Administration. With a maiden cruise in 1962, the vessel cost a little more than $18 million to build, but the 74-megawatt nuclear reactor added nearly $30 million to the price tag. The ship could carry 60 passengers, 124 crew, and over 14,000 tons of cargo around 300,000 nautical miles using one set of 32 fuel elements. What was it like onboard? The video below gives a glimpse of nuclear cruising in the 1960s.

If you want some more modern views of the vessel, NPR recently toured it at its current home in Baltimore and they have great photos.

Tech

Nuclear propulsion for warships is nothing new, of course. But the Savannah is one of only a handful of civilian ships to carry a reactor, and most of those were either Russian icebreakers or cargo ships. Unlike a military reactor, Savannah’s power plant was not made to be especially compact or shock resistant but had safety and serviceability in mind.

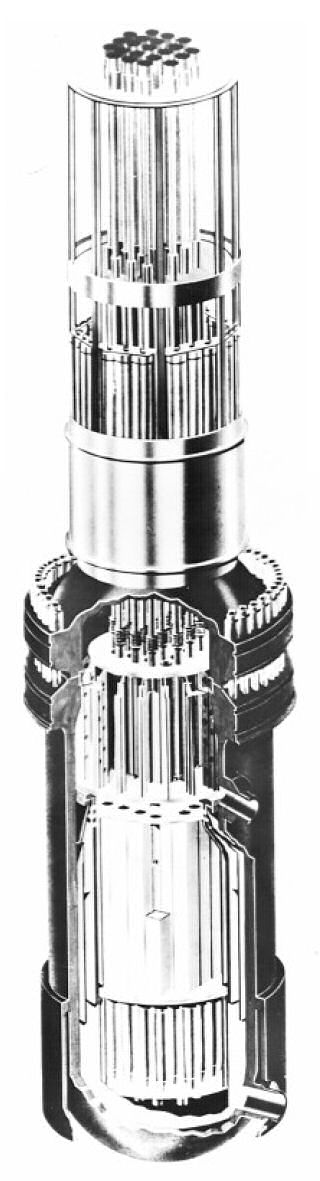

The reactor compartment was near the center of the vessel. It was possible to refuel the reactor from access above the compartment. The reactor was a tall cylinder inside a 50-foot-long containment vessel that was 35 feet in diameter. The steel vessel was up to 4 inches thick and could handle up to 186 PSI. Shielding included four feet of concrete, six inches of lead, and six inches of polyethylene. There was also 24 inches of collision shielding built from steel and redwood.

The fuel was low-enriched uranium. Each of the 32 fuel elements had 164 uranium oxide pellets contained in helium. The elements around the edge of the array were enriched to 4.6%, but the central elements were at 4.2%. A set of 21 control rods could fully insert into the core with electric motors in less than two seconds. The entire thing was 17 feet high.

The ship’s screw runs on steam generated by the heat from the nuclear reactor. A 35 ton gear that drives the screw is a precision-machined beast you can see in the video below. Watching the ship being built in that same video, you’d hardly know the ship had a nuclear reactor onboard.

Economics

The ship had 30 staterooms for passengers. That seems small by today’s super ship standards, but at the time, that was a respectable number for a luxury cruise ship. The dining room could seat 100 passengers, and many rooms, like the library, could convert to a movie theater or pool. The ship was a demonstration and was heavy on style but short on cargo capacity.

One of the problems with the ship is that it required a larger crew, many with unusual special training. In fact, the normal deck officers became unhappy that the nuclear engineering staff pay were paid better, and a strike stopped the ship for a while in Galveston. This caused the Maritime Administration to select a new operator, leading to further delays as they had to train a new crew.

The ship was named after the SS Savannah, the first steamship to cross the Atlantic. Both ships were not commercially successful but paved the way for new technology. In fact, as the world seeks to reduce carbon emissions, there is talk of civilian ships using nuclear power again.

Where Is It Now?

The Savannah traveled about 450,000 nautical miles during its lifetime. By 1965, passenger service ended after carrying a total of 848 passengers. For three more years, the ship carried cargo, being refueled once in Galveston, Texas. Once the ship was removed from service in 1972, it bounced around a bit. The city of Savannah was going to make it into a hotel. When that fell through, the ship rested in Galveston for a bit before winding up a museum ship in South Carolina. Eventually, the ship would need nearly a million dollars of renovation and wound up in Baltimore.

The fuel pellets left the ship in 1975, and the reactor found a final resting spot in Utah in 2022. Indeed, disposing of fuel and the power plant may be the largest expense of operating a ship like this.

Was the ship a success or a failure? It depends on your criteria. As a goodwill ambassador, it was a success. As a technology demonstrator, we think it worked well. It hasn’t ushered in the atomic age of shipping. But that may be just because it was a little too early. New smaller and safer reactors may well bring Savannah a lot of technological cousins in the future.

![retrotechtacular:-the-nuclear-cruise-ship-of-the-future-earns-glowing-reviews-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/131958-retrotechtacular-the-nuclear-cruise-ship-of-the-future-earns-glowing-reviews-hackaday.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)