Predicting the A-Bomb: The Cartmill Affair [Hackaday]

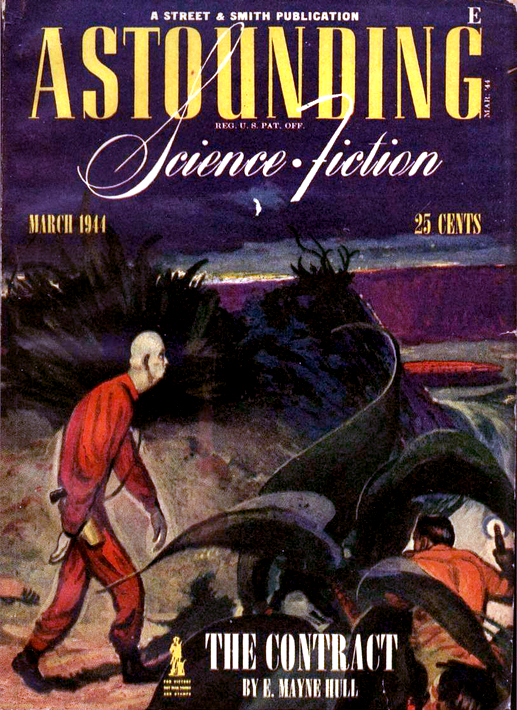

There’s an upcoming movie, Argyle, about an author whose spy novels are a little too accurate, and she becomes a target of a real-life spy game. We haven’t seen the movie, but it made us think of a similar espionage caper from 1944 involving science fiction author Cleve Cartmill. The whole thing played out in the pages of Astounding magazine (now Analog) and involved several other science fiction luminaries ranging from John W. Campbell to Isaac Asimov. It is a great story about how science is — well, science — and no amount of secrecy or legislation can hide it.

In 1943, Cartmill queried Campbell about the possibility of a story that would be known as “Deadline.” It wasn’t his first story, nor would it be his last. But it nearly put him in a Federal prison. Why? The story dealt with an atomic bomb.

Nothing New

By itself, that’s probably not a big deal. H.G. Wells wrote “The World Set Free” in 1914, where he predicted nuclear weapons. But in 1914, it wasn’t clear how that would work exactly. Wells mentioned “uranium and thorium” and wrote a reasonable account of the destructive power:

When he could look down again it was like looking down upon the crater of a small volcano. In the open garden before the Imperial castle a shuddering star of evil splendor spurted and poured up smoke and flame towards them like an accusation. They were too high to distinguish people clearly, or mark the bomb’s effect upon the building until suddenly the facade tottered and crumbled before the flare as sugar dissolves in water.

In fact, other earlier stories also predicted bombs, including 1941’s “Solution Unsatisfactory” by Anson MacDonald, a pseudonym for Robert Heinlen. So why was Carmill’s story of interest to the FBI?

The Story

If you want to read the short story, you can do so thanks to the Internet Archive. Remember, science fiction was simpler then. The major groups in the story are the Sixa and the Seillia. If these don’t mean anything to you, try spelling them backward. Presumably, war-time censors didn’t. We’ll wait.

The two groups are at war, and apparently, both have mastered the atomic bomb. While one side tries to deploy it and fails, the other side refuses, believing it to be amoral. By itself, this is just another story and means no more than Star Trek postulating a photon torpedo.

The description of the bomb and the issues of producing one is what drew attention:

“Have you heard of U-235 ? It’s an isotope of uranium.”

“Who hasn’t?”

“All right. I’m stating fact, not theory. U-235 has been separated in quantity easily sufficient for preliminary atomic-power research, and the like. They got it out of uranium ores by new atomic isotope separation methods; they now have quantities measured in pounds. By ‘they’, I mean Seilla research scientists. But they have not brought the whole amount together, or any major portion of it. Because they are not at all sure that, once started, it would stop before all of it had been consumed — in something like one micromicrosecond of time.”

. . .

“Now the explosion of a pound of U-235,” he said, “wouldn’t be too unbearably violent, though it releases as much energy as a hundred million pounds of TNT. Set off on an island, it might lay waste the whole island, uprooting trees, killing all animal life, but even that fifty thousand tons of TNT wouldn’t seriously disturb the really unimaginable tonnage which even a small island represents.

“The trouble is, they’re afraid that that explosion of energy would be so incomparably violent, its sheer, minute concentration of unbearable energy so great, that surrounding matter would be set off. If you could imagine concentrating half a billion of the most violent lightning strokes you ever saw, compressing all their fury into a space less than half the size of a pack of cigarettes — you’d get some idea of the concentrated essence of hyperviolence that explosion would represent. It’s not simply the amount of energy; it’s the frightful concentration of intensity in a minute volume.

“The surrounding matter, unable to maintain a self-supporting atomic explosion normally, might be hyper-stimulated to atomic explosion under U-235’s forces and, in the immediate neighborhood, release its energy, too. That is, the explosion would not involve only one pound of U-235, but also five or fifty or five thousand tons of other matter. The extent of the explosion is a matter of conjecture.”

100vw, 400px”></a><figcaption class=) Deadline’s secret mission glider. Art by Orban

Deadline’s secret mission glider. Art by OrbanThe protagonist doing most of the speaking is on a secret mission to destroy the enemy’s bomb, which contains 16 pounds of U-235. He later describes using two hemispheres to separate the reaction mass and neutron shielding when the bomb is inactive.

Apparently, Cartmill’s original idea was just some “super bomb,” but Campbell, who attended MIT and had a physics degree from Duke, passed him background information on atomic bombs gathered from public information.

Los Alamos

Many at Los Alamos read science fiction. In fact, it is rumored that Cambell had noticed a swell in change of address forms to New Mexico and had surmised that something was going on there, although he apparently never mentioned it.

When the story came out in February 1944, workers at Los Alamos started to talk about it. After all, it had concerns very similar to their own. Should the bomb be used? It also identified separation as a major roadblock and the fear that a chain reaction might not stop.

A security officer made note of the conversations and reported it to the FBI. An investigation into Cartmill and Campbell resulted. The FBI even looked into their acquaintances, including Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein.

Investigation and Retrospect

In retrospect, Cartmill’s bomb design probably wouldn’t work, but that might not have been clear in 1944. But it did predict the problem of isotope separation and hinted at several other realistic details.

The amount of effort spent on investigating the story was impressive. The FBI found that Campbell had lunch with an engineer working on an unrelated classified project and interviewed him, too. It didn’t help that Campbell initially claimed all the technical content of the story was due to his influence, while Cartmill claimed he was the architect of the faux nuclear device. Later letters showed that the ideas were, in fact, Campbell’s.

At least one investigator was convinced that some of the story had to be from classified research. However, the FBI never found a link between anyone involved and the Manhattan Project that produced the bomb. In the end, the feds forbade Campbell from running any more stories about uranium or atomic power until after the war.

Yesterday’s science fiction is sometimes tomorrow’s facts. We’ve seen reasonably good approximations of cell phones, self-driving cars, virtual reality, and more. Then again, fiction doesn’t anticipate everything. But just as legislators can’t change the value of pi, keeping science secret is rarely effective for very long. The inquisitive nature of scientists and engineers and the fact that nature keeps no secrets on purpose make it a futile effort.

There was real concern that one nuclear chain reaction could end everything, but that’s not the case or you wouldn’t be reading this. Even today, though, extracting isotopes isn’t child’s play.

![predicting-the-a-bomb:-the-cartmill-affair-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/163295-predicting-the-a-bomb-the-cartmill-affair-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)