Measuring Trees Via Satellite Actually Takes A Great Deal of Field Work [Hackaday]

Figuring out what the Earth’s climate is going to do at any given point is a difficult task. To know how it will react to given events, you need to know what you’re working with. This requires an accurate model of everything from ocean currents to atmospheric heat absorption and the chemical and literal behavior of everything from cattle to humans to trees.

In the latter regard, scientists need to know how many trees we have to properly model the climate. This is key, as trees play a major role in the carbon cycle by turning carbon dioxide into oxygen plus wood. But how do you count trees at a continental scale? You’ll probably want to get yourself a nice satellite to do the job.

How Many Are There?!

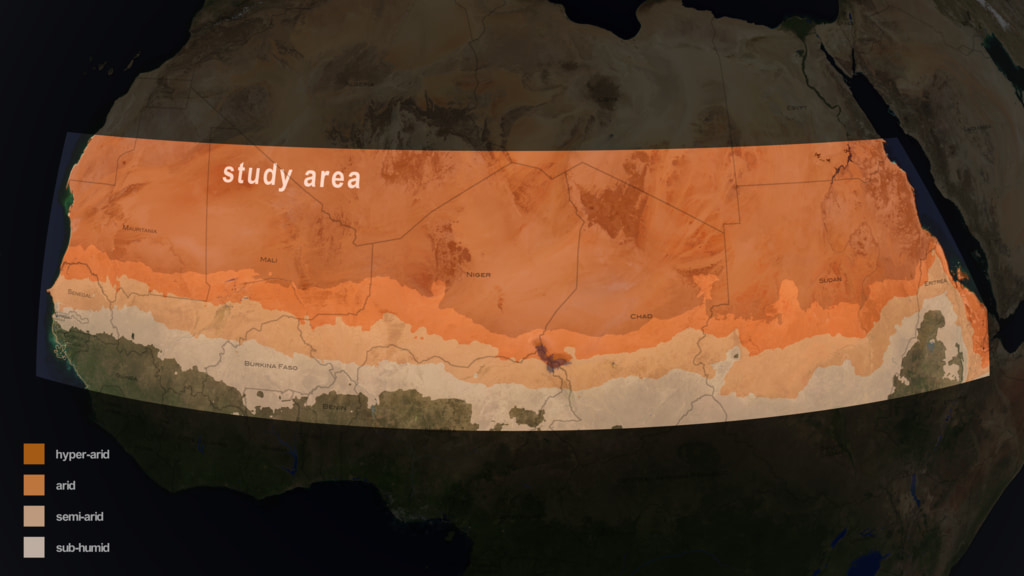

Thankfully, some of the bright minds over at NASA are on the job. In partnership with an international team of scientists, they have been mapping out trees across vast tracts of Africa. The aim of the project was to get an idea of just how much scarbon is stored across Africa’s drylands, as opposed to the dense tropical rainforests in the region.

To count the tree populations across such a wide area, the team relied on high-resolution satellite imagery from commerical providers. Once the purview of governments only, now it’s easy enough to stump up some cash and get all the high-resolution space photography you could possibly imagine. The team sourced a dataset of 326,000 satellite images from the QuickBird-2, GeoEye1, WorldView-2, and Worldview-3 satellites, all run by Maxar Technologies. The images had a resolution of 50 centimeters, allowing for the identification of individual trees.

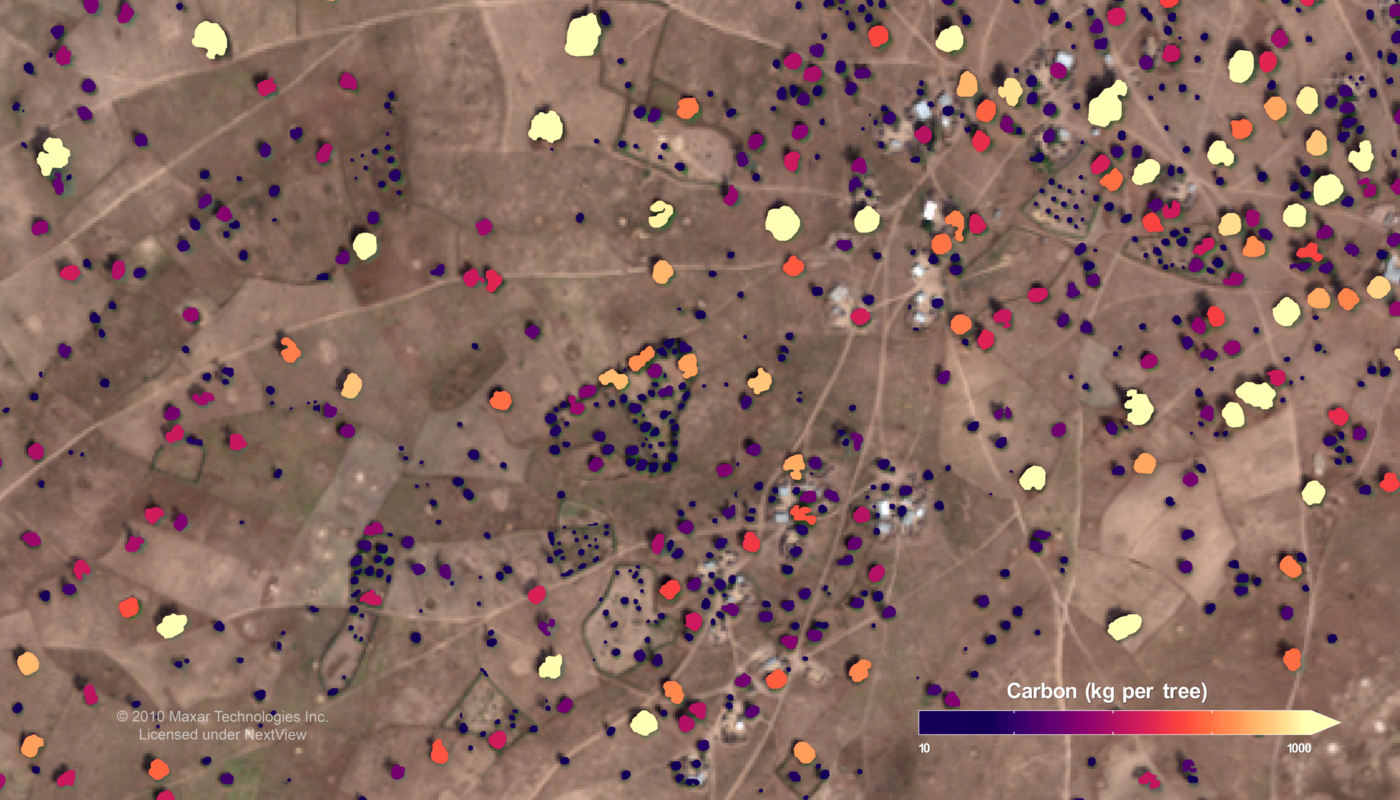

Researchers then used an artificial intelligence algorithm to count trees in the images. This model had to be trained first, of course. A sub-team at the University of Copenhagen was charged with this role, using data from 89,000 individual trees to teach the AI how to identify trees and their carbon content from satellite images. The model was taught to identify trees by their crown of green leaves, along with an adjacent shadow. The latter detail is key to differentiating a tree from a small shrub or grass sitting at ground level. The machine-learning model had its output tested by comparing it with human assessors, with the model proving to be 96.5% accurate compared with human measurements of tree-crown area.

Armed with the measurement of crown area, researchers can then extrapolate this with a statistical model to get an idea of how much carbon that given tree has stored. This statistical model was created by a group at the University of Toulouse, which assessed 30 unique tree species. By measuring the mass of leaves, wood, and roots, and comparing it to crown area, the team formed a model that could take crown measurements from satellite data and turn it into carbon storage figures. This took a great deal of work, involving going out to dig up and literally measure real trees in the field.

Speaking on the matter, lead scientist Compton Tucker noted this method has provided a far more accurate idea of carbon storage in the African drylands than was previously available. Earlier efforts had gotten confused between grass or shrubs and actual trees pictured in satellite images. “That led to over-predictions of the carbon there,” stated Tucker. In contrast, the researchers now had a much finer analysis. Our team gathered and analyzed carbon data down to the individual tree level across the vast semi-arid regions of Africa or elsewhere – something that had previously been done only on small, local scales,” said Tucker.

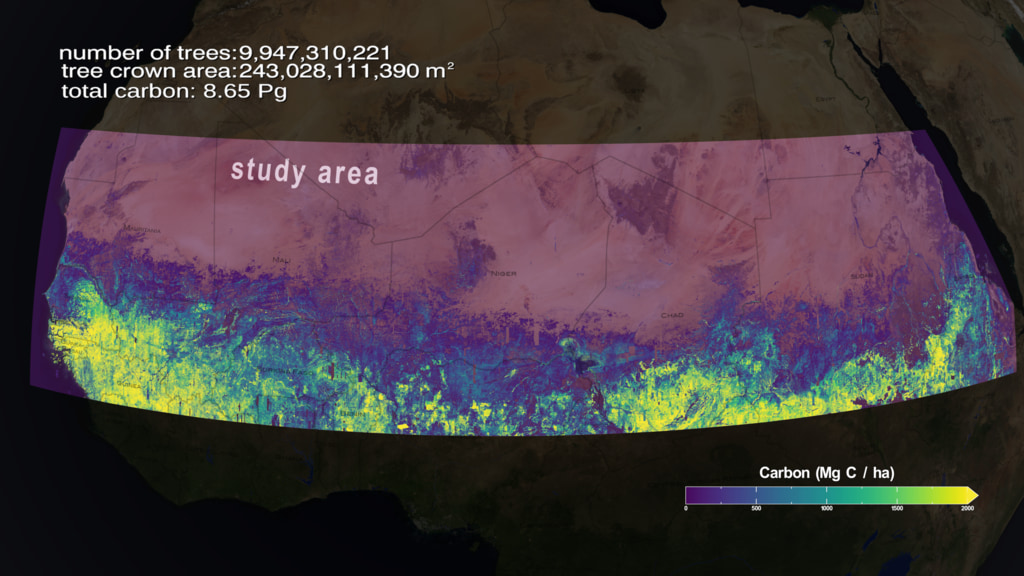

It might sound easy to simply download some satellite images, run an algorithm, and count some trees. The reality is far more complex. The scientists had to do plenty of work out in the real world to create the models that underpin this analysis. As a result, though, we now have a far better understanding of carbon storage across the drier parts of Africa. Researchers learned that while individual trees store somewhat less carbon than initially predicted, there are also a lot more trees out there than previously understood. The final estimate was that the trees of the African drylands store around 0.84 petagrams of carbon, or roughly 840 million metric tons. That’s approximately 926 million US tons, if you’re used to measuring continents worth of trees in imperial units.

The research team has openly shared its work, so you can read the full paper and dive into the data as you wish. This knowledge should help incrementally improve climate models for scientists around the world.

![measuring-trees-via-satellite-actually-takes-a-great-deal-of-field-work-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/169137-measuring-trees-via-satellite-actually-takes-a-great-deal-of-field-work-hackaday.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)