Luna 25’s Demise: Raising Fundamental Questions About Russia’s Space Program [Hackaday]

The recent news that Russia’s Luna 25 Moon lander had made an unexpected lithobraking detour into the Moon’s surface, rather than the expected soft touchdown was met by a variety of responses, ranging from dismay to outright glee, much of it on account of current geopolitical considerations. Yet politics aside, the failure of this mission casts another shadow on the prospects of Russia’s attempts to revive the Soviet space program after a string of failures, including its ill-fated Mars 96 and Fobos-Grunt Mars missions, the latter of which also destroyed China’s first Mars orbiter (Yinghuo-1) and ignited China’s independent Mars program.

To this day, only three nations have managed to land on the Moon in a controlled fashion: the US, China, and the Soviet Union. India may soon join this illustrious list if its Chandrayaan-3 mission’s Vikram lander dodges the many pitfalls of soft touchdowns on the Moon’s surface. While Roscosmos has already started internal investigation, it does cast significant doubt on the viability of the Russian Luna-Glob (‘Lunar Sphere’) lunar exploration program.

Will Russia manage to pick up where the Soviet Union left off in 1976 with the Luna 24 lunar sample return mission?

Post-Space Race

The period of the 1950s leading into the 1970s was one of breakneck innovations and experimentation as one first after the other got achieved. Here the USSR outperformed the US on many accounts, achieving the first artificial satellite, first lunar spacecraft and orbiter, first human spaceflight and first spacewalk. As the USSR suffered setbacks with its N1 heavy rocket, however, it had to relent the first manned flights to the Moon, instead shifting its attention to more robotic flights to Mars (first soft touchdown on Mars with Mars 3), the Moon (Luna 16’s first robotic sample return mission) and the highly notable soft touchdowns on Venus with the Venera landers.

During the 1970s, the USSR developed a range of highly successful space stations with the Salyut program that led to the modular space station Mir and the successor Mir 2, the latter of which became known as the International Space Station (ISS). The irony of this is perhaps that although we refer to the ‘Russian section’ of the ISS, it’s effectively a Soviet-built core (the Zvezda module being the Soviet-era Mir 2 core module), with the additional modules following Soviet designs including the Soviet-designed auto-docking system.

So if the ‘Russian space station’ is really just a Soviet space station with a different flag glued on top of the old Soviet one, what does this tell us about Russia’s Martian and Lunar programs? In how far are they different from their Soviet predecessors, when Roscosmos has insisted on following the same internal designations for the Luna 25 and future planned missions?

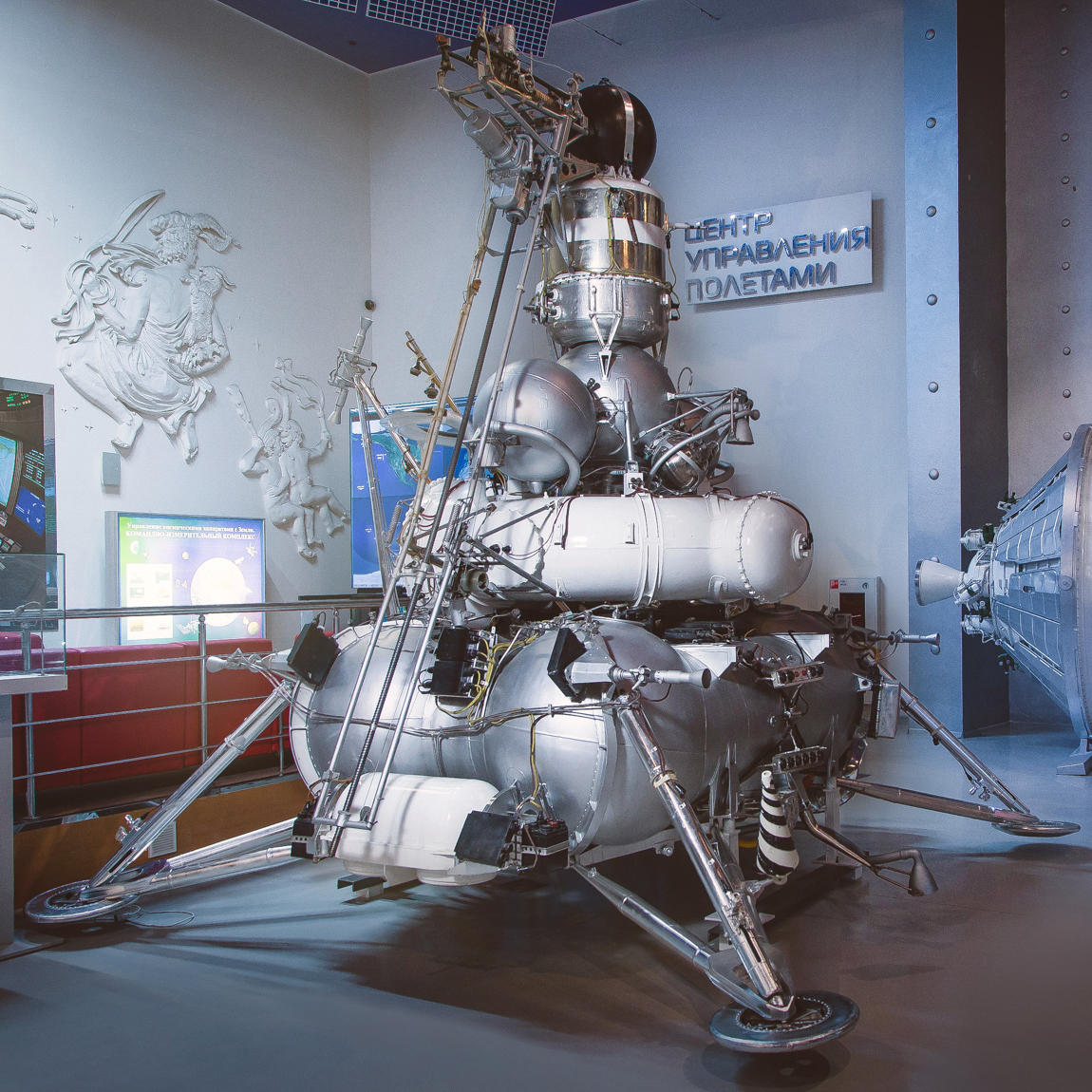

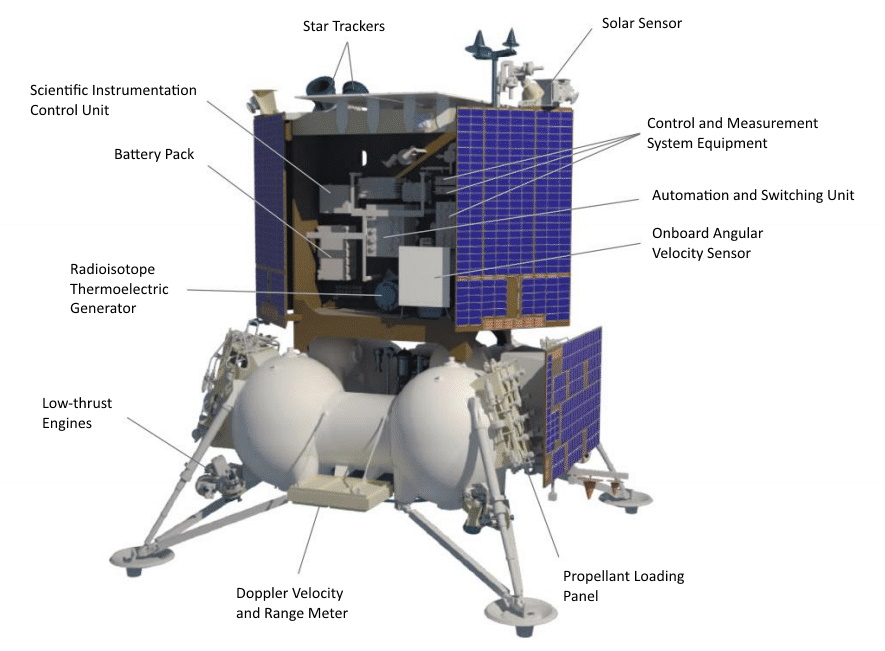

The Luna 25 Lander

The last Luna program mission happened in 1976, with not only the fall of the Soviet Union throwing a spanner in the works since then, but also a few generations of new engineers earning their degree and retiring since then, not to mention the many who found employment outside of Russia. For the Luna-Glob program this essentially meant having to start from scratch, using old paper drawings and possibly fuzzy recollections from whoever once worked at the same NPO Lavochkin aerospace company that manufactured Luna 9 through 24, as well as the ill-fated Luna 25.

If we compare Luna 24 with Luna 25, we can get some idea of in how far it is a continuation rather than a pale imitation. The former had a launch mass of 5,800 kg compared to the latter’s 1,750 kg, with Luna 24 featuring the sample return stage (weighing 520 kg), sample collection system and some basic scientific instruments plus a video camera.

Meanwhile the Luna 25 probe had a 30 kg payload of various scientific instruments that can analyze scooped up lunar regolith, as well as a range of other aspects of the lunar surface. These include a laser mass analyzer assisted by an infrared spectrometer to determine the components in the lunar regolith, a neutron-based scanning tool to analyze the regolith in-situ, plus multiple instruments to study the lunar exosphere (very thin atmosphere), all packed together as a miracle of modern miniaturization compared to the state of the art back in the 1970s, when unreliable singular transistors led to the loss of many Soviet spacecraft.

The Luna 25 spacecraft also would seem to share many characteristics with its Soviet-era predecessor, which would seem to include the propulsion system that’s supposed to guide the craft into a suitable landing orbit. Unfortunately, based on the comments made by Roscosmos it would seem that either a string of incorrect trajectory adjustment commands were sent to the spacecraft, or some kind of malfunction occurred which led to its unfortunate lithobraking course. Clearly, even if it’s proven Soviet technology with a modern payload strapped to it, it is not immune to what at this point in time could be a simple human error or conceivably an assembly error, not unlike what happened to the manned Soyuz MS-10 launch to the ISS in 2018 that nearly killed both crew members due to an apparent assembly error.

Too Little Too Late?

Perhaps the optimistic take on this failure is that by avoiding sending wrong commands to the lander it could just work next time. The problem is that Luna 25 already took many years longer than originally scheduled, to the point where ESA dropped cooperation with Roscosmos and pulled an instrument off the lander. Meanwhile the Luna 26 orbiter (tentatively 2027) and Luna 27 lander (tentatively 2028) are likely to be pushed back while Roscosmos considers a possible replacement for Luna 25. Yet the major question is whether it matters at all, considering that China has seemingly leap-frogged Russia.

China’s Lunar Exploration Program began in 2007 with the Chang’e 1 orbiter, followed by the Chang’e 2 orbiter in 2010. Since then the Chang’e 3 lander and Yutu 1 rover touched down softly on the lunar surface in 2013. Subsequently Chang’e 4 landed in 2018 on the far side of the Moon as a world’s first, along with its Yutu 2 rover, both of which are still active today. The Chang’e 5 sample return mission was a complete success in 2020, which will be followed up by the Chang’e 6 sample return mission in 2024 and the 2026 Chang’e 7 mission featuring an orbiter, lander, rover and a hopping probe, all focused on the Moon’s south pole, which is the target of many current and upcoming Moon missions.

All of these are in preparation for the Chang’e 8 mission that is intended to launch in 2028 and which should feature a robotic laboratory to attempt in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) and other experiments prior to a manned Moon mission and attempts to establish a Moon base. Also of note is that while Russia’s Moon program has been largely cut off from the international scientific community, China’s program features international payloads, such as the German Lunar Lander Neutron and Dosimetry experiment on Chang’e 4. The fruits of this cooperation can be found in publications such as Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, with this 2022 paper by Zigong Xu and colleagues providing insights on primary and albedo protons on the far side of the Moon.

Similarly, the Swedish LINA-XSAN payload was also pulled from Luna 25 and flew on Chang’e 4 instead.

Eyes On India

Although it’s never wise to count one’s chickens before all fragile eggs have landed safely on lunar regolith, there’s a good chance that India’s Moon program will bear fruit starting with Chandrayaan-3 this month, paving the road for a new era of Moon exploration in which China, India and private companies will be most firmly represented. It is highly likely that ESA and NASA will cooperate with these programs, providing scientific instruments that can thus make their way to the lunar surface in absence of a relevant European or North-American Moon program.

In this regard Luna 25 could be seen as the last bitter-sweet hurrah to the once proud Soviet engineering prowess that formed such a fundamental foundation for space today, including the seeds that would go on to form the Chinese and Indian space programs. If it are those respective Moon programs that can thus be considered the true spiritual successors of the Soviet space program, then Luna 25 was the definite sign that the last embers of the Soviet space program within the borders of the Russian Federation have now turned cold.

Heading image: A Soyuz-2.1b rocket booster with a Fregat upper stage and the Luna 25 lunar lander blasts off from a launchpad at the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Amur Oblast, Russia.

![luna-25’s-demise:-raising-fundamental-questions-about-russia’s-space-program-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/138621-luna-25s-demise-raising-fundamental-questions-about-russias-space-program-hackaday.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)