Jenny’s Daily Drivers: Slackware 15 [Hackaday]

As a recent emigre from the Ubuntu Linux distribution to Manjaro, I’ve had the chance to survey the field as I chose a new distro, and I realised that there’s a whole world of operating systems out there that we all know about, but which few of us really know. Hence this is the start of what I hope will be a long-running series, in which I try different operating systems in my everyday life as a Hackaday writer, to find out about them and then to see whether they can deliver on the promise of giving me a stable platform on which to earn a living.

For that they need an internet connection and a web browser up-to-date enough to author Hackaday stories, as well as a decent graphics package. In addition to using the OS every day though, I’ll also be taking a look at what makes it different from all the others, what its direction and history is, and how user-friendly it is as an experience. Historical systems such as CP/M are probably out of the question as are extremely esoteric ones such as the famous TempleOS, but this still leaves plenty of choice for an operating system tourist. Join me then, as I try all the operating systems.

A Distro From The 1990s, Today

When deciding where to start on this road, there was an obvious choice. Slackware was the first Linux-based distribution I tried back in 1995, I’m not sure which version it was , but it came to me via a magazine coverdisk. It was by no means the first OS that captured my attention as I’d been an Amiga user for quite a few years at that point, but at the moment I can’t start with AmigaOS as I don’t have nay up-to-date Amiga-compatible hardware.

July 2023 also marks the 30th anniversary for the distro making it the oldest one still in active development, so this seems the perfect month to start this series with the descendant of my first Linux distro. Slackware 15 comes as a 3.8 GB ISO file download for 64-bit computers, and my target for the distro was an old desktop PC with an AMD processor and a big-enough spinning rust hard disk which had been a high-end gaming system a little over ten years ago. Not the powerhouse it once was, but it cost me nothing and it’s adequate for my needs. Installed on a USB Flash drive the Slackware installer booted, and I was ready to go.

Slackware’s philosophy is stated as providing the most UNIX-like Linux distro, and to contain packages most faithful to their upstream sources without modifications. This isn’t a distro that’s trying to set itself apart with flashy desktop environments or semi-proprietary packaging systems, instead you’re getting the straightforward GNU/Linux experience from a pre-assembled distribution.

What this means in practice is that it’s a powerful and usable distro that doesn’t require a beard down to the waist to install, but it’s also a distro which expects the user to be prepared to get their hands dirty to some extent. This is immediately obvious when starting the installation, because the first requirement is to run fdisk and partition the destination disk. Pretty much every major distro will now have an option to let it choose the partitioning automatically for you, but Slackware users must do it for themselves. It’s not too difficult and anyone prepared to pull up fdisk’s help screens and maybe consult the web for assistance can pretty quickly make a main partition and a swap partition, but the overall feel is the same as distro installation in the 1990s.

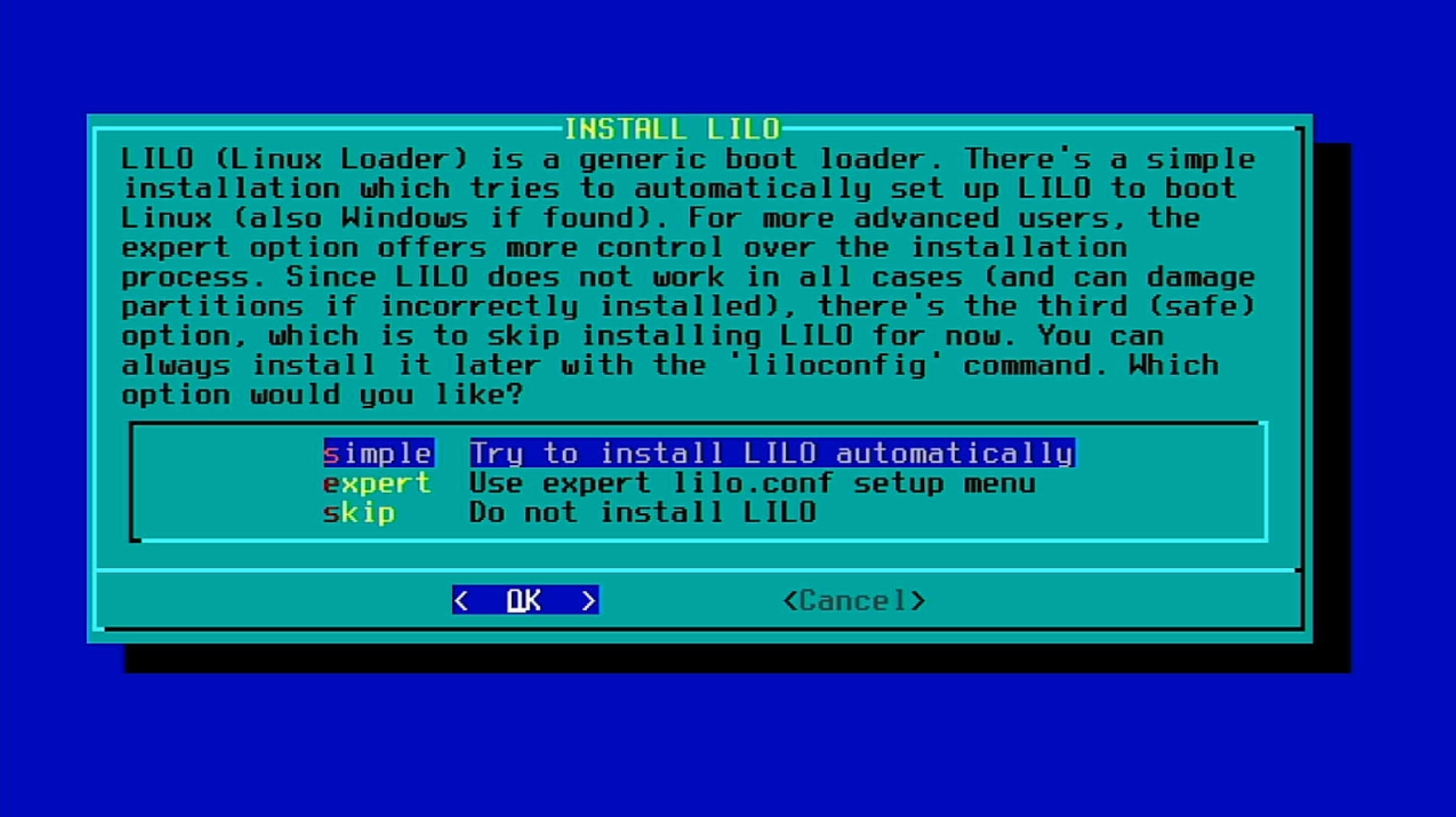

The rest of the install is through a straightforward text-based installer which is easy enough to use, but those ’90s vibes are enhanced when it installs lilo instead of GRUB as a bootloader. I can’t remember, but I think it must be at least 20 years since I last had a machine with lilo on it. Finally it leaves me booted into my new system at the prompt, with only the root user as a login. I must create my normal everyday user myself with the adduser script, and once I’m logged in with normal-strength privileges I must type startx at the prompt if I want the graphical desktop. Nobody is holding my hand on my Slackware journey.

Not A Distro For The Novice

I now have a Slackware machine in front of me, and it’s a modern full-featured Linux distro so of course it does a fine job of being a daily driver. I chose the KDE desktop, and I can go straight into working on Hackaday. There’s thus little point in discussing its usability for my work as I might with some operating systems, instead it’s worth looking at the other ways I interface with my OS. What’s it like installing and updating software on a Slackware machine?

Just as on a Debian machine I’d reach for apt and on a RedHat descendant I’d reach for rpm, on Slackware the package management is done through slackpkg. Slackware packages are compressed archives containing all the necessary files in their paths ready for extraction into the filesystem, and reading up on them I was mildly alarmed as someone used to other distros to note that resolving dependency issues isn’t part of the equation.

Running slackpkg update refreshes the list of latest software, and the first time I ran it I had to uncomment a line in the mirrors file before it would let me do that. Then it was time for slackpkg upgrade-all, to upgrade everything to its latest version. I’m used to Debian, so I’d do the equivalent there on a new install with apt upgrade.

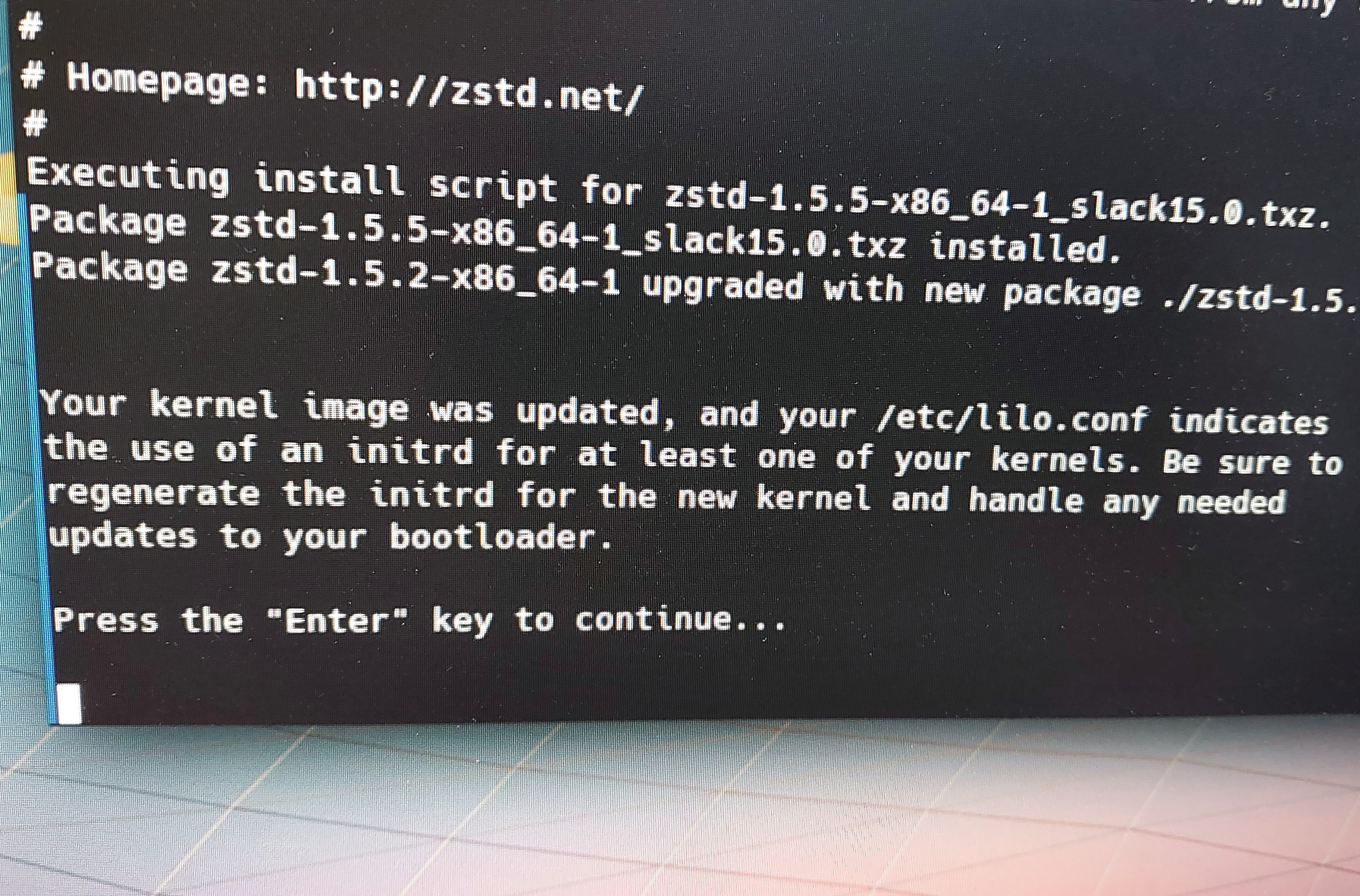

On many distros this would be a straightforward process of waiting for the packages to install and getting on with life, but here again we’re reminded that this is not a distro for the faint hearted. It casually informs me that since the kernel has updated I must rebuild my initrd and run lilo again, my machine is essentially now broken without more wizardry. It’s not impossible and a very quick web search reveals /usr/share/mkinitrd/mkinitrd_command_generator.sh which generates the commands to fix it, but it’s not a task for everyone.

My brief sojourn into Slackware nearly three decades after I first tried it has been a success, and I have a machine with a distro that’s the match for any other. It’s been an odd experience though, one of traveling back to the 1990s when Linux distro installs required patience and some level of work. As a daily driver it’s without fault, indeed I’ve written most of this piece on it, but for anyone else perhaps I’d describe it for those unafraid of diving into their distro rather than simply using it. Give it a try, you’ll come away learning stuff.

![jenny’s-daily-drivers:-slackware-15-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/132158-jennys-daily-drivers-slackware-15-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)