Do Bounties Hurt FOSS? [Hackaday]

As with many things in life, motivation is everything. This also applies to the development of software, which is a field that has become immensely important over the past decades. Within a commercial context, the motivation to write software is primarily financial, in that a company’s products are developed by individuals who are being financially compensated for their time. This is often different with Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) projects, where the motivation to develop the software is in many cases derived more out of passion and sometimes a wildly successful hobby rather than any financial incentives.

Yet what if financial incentives are added by those who have a vested interest in seeing certain features added or changed in a FOSS project? While with a commercial project it’s clear (or should be) that the paying customers are the ones whose needs are to be met, with a volunteer-based FOSS project the addition of financial incentives make for a much more fuzzy system. This is where FOSS projects like the Zig programming language have put down their foot, calling FOSS bounties ‘damaging’.

Bounty Hunting

Within this absolutely volatile and inflammatory topic, it is probably a good idea to first nail down what is meant with a ‘bounty’, as there are a number of possible interpretations just within the field of software development. Perhaps the most well-known is the concept of bug bounty programs, where someone who discovers a flaw in the software product or service of a company can get some kind of (monetary) reward. This reward is supposed to be there to both motivate security researchers to discover new bugs, and to report said bugs to the company rather than to let less scrupulous individuals use them for ill-gotten gains.

In a way this makes such a bounty program somewhat into a modern equivalent of the old tradition of bounty hunters, yet it is quite distinct from bounty programs that target the development of software features rather than the discovery of bugs. When it comes to motivating the development of new features we can distinguish two major types of incentives:

- A community bounty to submit a feature patch to the project.

- A monetary reward given to the project’s developer(s) upon completion of the new feature.

In the Zig project‘s blog post we can see that they have no issue with bug bounties, which is understandable. Despite some issues with bug bounty programs over the decades, in general they are a net positive incentive which can create a healthy relationship between security researchers and developers. After all, even the best-run software project will inevitably have some bugs in the Golden Master release version that gets pushed out into the world, some of which you’d rather hear about from a reputable researcher than read about in the media.

In contrast, the notion of community bounties is branded as being essentially harmful and something the Zig developers caution against. Rather than providing a friendly, cooperative atmosphere, such bounties are bound to invite hastily developed, poorly considered implementations where the main measure of ‘success’ is whether or not all test cases light up green. Add to this the possibility of the project developers having to judge and likely reject various competing submissions, and it would seem reasonable to conclude that only the security researchers are winning out in such a scenario.

Staking Claims

The idea of putting up software bounties to promote the development of features is not a new thing by any stretch, with for example the GNU Hurd project in 2011 spelling out why they feel that bounties are a great idea. Yet the website that particular project references – FOSS Factory – appears to have been essentially dead since about 2008, or three years before the GNU Hurd project even promoted its use.

A more current example of a software bounty website is Bountysource, which currently is still actively accepting new bounties. However, after having been purchased and sold on again by a number of cryptocurrency companies it’s currently in hot water for not paying out the bounty money which it is supposed to hold in escrow. This was apparently an issue back in 2020 already, with some projects moving to GitHub Sponsors, which interestingly enough is essentially the inverse of a bounty system as it involves donating to a project.

Rather than being strictly a donationware system, however, it is duly noted by Naomichi Shimada and colleagues in a 2022 study that GitHub Sponsors turns a project into sponsorware. Although the difference between donating and sponsoring can seem academic to some, the latter has definite expectations of returns, no matter in what form. In the study by Shimada et al., these differing expectations between project managers and those who sponsor or otherwise contribute to a project other than as a developer are addressed as a potential issue that should be kept in mind by project owners before enabling sponsorships.

Commercial FOSS

A viable way to get the financial cost of developing software features settled is covered in detail by Brad Collette of the Ondsel (FreeCad) core team. Although the points raised against community bounties are pretty much the same as those raised by the Zig developers, the suggested way which does work essentially involves crowdfunding, with the Krita project provided as a shining example.

Essentially the project developers will get together to figure out which features could or should be implemented in the next major release and pitch this to the community. By running a crowdfunding campaign with stretch goals, the community can thus directly fund the new features while any stretch goals are similarly decided on by the community through their financing. Although the project is still technically FOSS, this makes the community (users) an integral part of the project by making them stakeholders in the project.

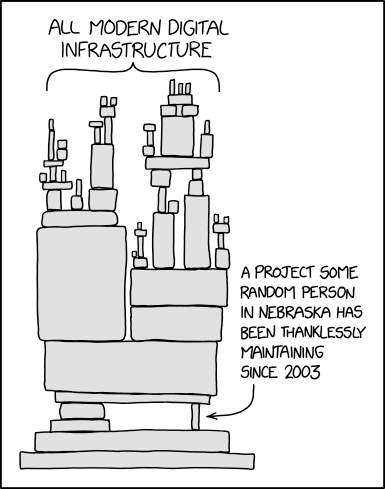

Interestingly, this isn’t far removed from how many big FOSS projects – such as the Linux kernel and the largest distributions – are funded. Although full of little pieces of hobby projects that may conceivably collapse the larger project if they ever developed an issue, these large FOSS projects are by and large sponsored and funded by the world’s wealthiest companies.

As an example, the Linux kernel is backed by the Linux Foundation’s sponsors, with in 2021 Huawei providing the most changesets and Intel contributing the most lines of code changed on the 5.10 kernel. In 2022, the 6.0 kernel saw Intel, AMD, Google and Linaro competing in the top 4 of each category. Overall, most FOSS development is directly paid for – often using in-house developers – by IT giants like Microsoft, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Intel and Google. This then clearly renders the question of software bounties moot for these kinds of FOSS projects when companies with billions of USD in revenue are footing the bill already.

Small FOSS

Reading through e.g. this 2021 discussion over at Hacker News on the topic of software bounties is also rather interesting as a way to gauge people’s feelings and experiences on the matter. The general consensus would appear to be that for FOSS projects that do not already have the backing of wealthy sponsors or similar, keeping the developer(s) behind them engaged and motivated is crucial.

Speaking as someone who has had their own middling success with some mildly successful FOSS projects, there is a certain rush that comes from people actually paying attention to, and even using your software in real commercial projects. Yet at the end of the day it is essential to differentiate whether a project is a hobby or a job, with the differentiator here being whether you are being paid to do work.

If you are a project owner, and you put out a crowdfunding request that ends up covering your projected feature implementation costs, even if it’s just to cover the rent and human/pet food, you take on the responsibility to get that feature implemented so that those who financially contributed are satisfied with the results.

If, however, someone creates a ticket in your GitHub project saying that they would ‘really like to see feature XZ implemented’, but no funding has been allocated, it’s still just your hobby project and you are free to ignore such tickets, or only take it on because it seems interesting as a challenge within the context of said hobby project.

A major risk with FOSS projects is FOSS exploitation, which most recently has become a rather hotly debated topic. Some companies are now moving away from very open FOSS licenses to more restrictive ones (like the GPL) as a result, as a way to combat other companies making money off something that was given away for free. This could be regarded as a natural response to such exploitation, as companies and individuals alike seek to protect themselves.

We are taught as children that ‘sharing is caring’, yet the concept of fairness is even more crucial. Although FOSS is sometimes portrayed as some kind of utopian dream of infinite free software, the harsh reality is that each line of code is still written and tested by human beings, each of whom need to eat, and deserve their fair due.

![do-bounties-hurt-foss?-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/144527-do-bounties-hurt-foss-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)