Could Moon Dust Help Reduce Global Temperatures? [Hackaday]

The impacts of climate change continue to mount on human civilization, with warning signs that worse times are yet to come. Despite the scientific community raising an early warning as to the risks of continued air pollution and greenhouse gas output, efforts to stem emissions have thus far had minimal impact. Continued inaction has led some scientists to consider alternative solutions to stave off the worst from occurring.

Geoengineering has long been touted as a potential solution for our global warming woes. Now, the idea of launching a gigantic dust cloud from the moon to combat Earth’s rising temperatures is under the spotlight. However, this very sci-fi solution has some serious implications if pursued, if humanity can even achieve the feat in the first place.

Cloud of Protection

The idea behind the proposal is simple. By reducing the energy input into the Earth from the Sun, we can better account for the Earth’s increased insulation in recent times. There are a variety of ways to achieve this, with the emission of sulfur dioxide aerosols an area of active research for many scientists. However, moon dust could serve in a very similar role, if properly distributed around the Earth.

Researchers have explored methods such as creating a large singular cloud of dust to protect the Earth. Dust particles floating in a cloud between the Sun and the Earth would help reduce the planet’s temperature by absorbing heat from the sun as well as scattering light away from the Earth. One study suggested that to effectively block enough sunlight to halt climate change, over 10 billion kilograms of dust per year, perhaps sourced from near-Earth asteroids, would need to be positioned at the L1 Lagrange point. Here, the gravitational tug of the sun and Earth cancel each other out, allowing objects to remain stationary.

However, continuous maintenance of the cloud would be necessary due to particles in the cloud being disrupted by the solar wind, gravitational effects, and radiation pressure from sunlight. A further problem is simply one of scale; the weight of dust required is over 700 times greater than the total mass humanity has launched into space to date. Getting all that dust into the right spot in orbit would require a huge number of launches; a logistical effort far eclipsing anything humanity has done before.

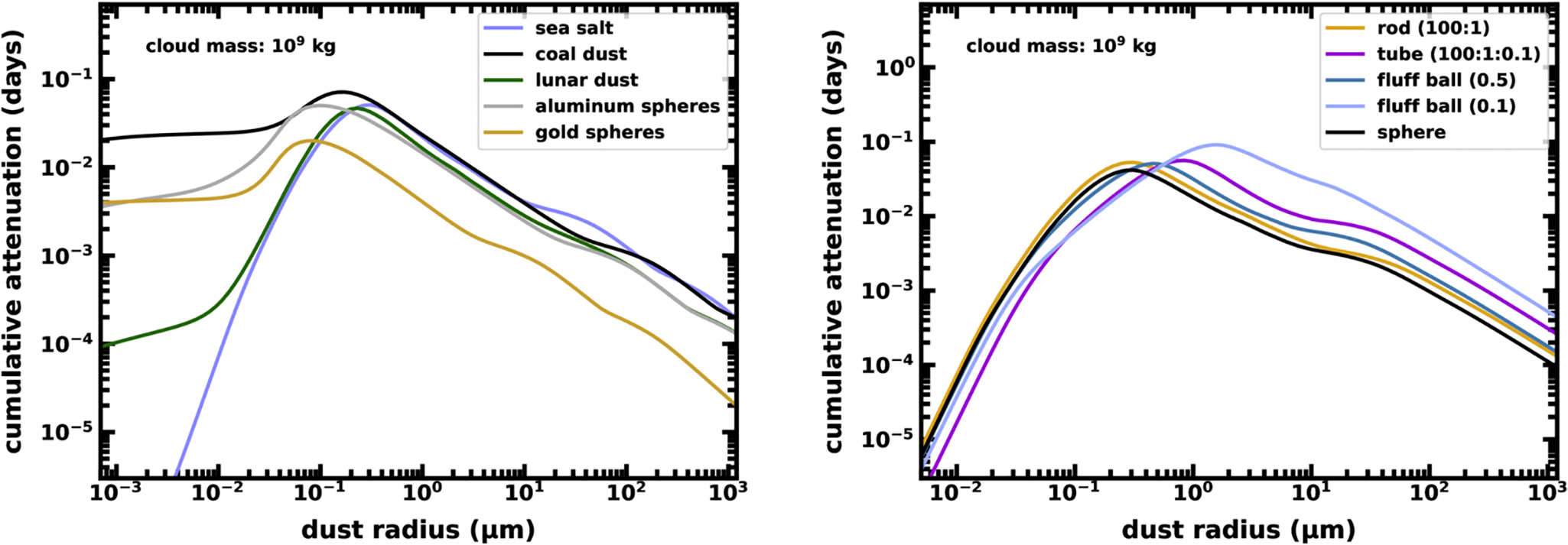

Another research paper published earlier this year in PLOS Climate suggests an alternative method. Thanks to recent computer simulations by Benjamin Bromley and his team at the University of Utah, a promising approach might be directly launching a steady stream of dust from the moon’s north pole on ballistic trajectories towards L1. These simulations indicated that each particle could block sunlight heading to Earth for approximately five days before scattering throughout the solar system. This offers a practicality benefit, too. The short-lived nature of the cloud means that it could be varied in its density or removed entirely in just a few days in order to control the intensity of its shading effect.

Of course, the logistics of deploying such a massive amount of dust would still remain a challenge. Bromley’s calculations are based on somewhat idealized particles, which would be manufactured in situ on the Moon. We lack the technology to do that right now, as well as the technology to launch these particles towards L1. Bromley hypothesizes that a railgun would be an effective method, given that it could be powered via solar panels placed on the Moon itself. It would, at the very least, be a far more efficient method than launching 10 billion kilograms of dust from Earth itself.

Hazards of Geoengineering

While these efforts sound promising, if far-out, there are caveats. For starters, it’s uncertain whether such a massive undertaking would be worth the effort. Even if we had the technology to create such a dust cloud, the effects may not be so simple. Even if it reduces Earth’s average temperatures, it could change sunlight distributions on the Earth in such a manner as to influence things like ocean currents, rainfall patterns, and other climate phenomenon. This could drastically impact agriculture and the livability of inhabited areas, with potentially disastrous effects for the global food supply. Global climate systems are so complex that it is difficult to model such diffuse effects with any real certainty.

The most significant concern, however, is the commitment this method requires. If we start geoengineering to counteract greenhouse gas output, it may become necessary to make it a near-permanent solution. Politically, any such sun shield could be used as a convenient excuse for halting emissions reductions. This could then leave Earth dangerously exposed to rapid temperature rise if the geoengineering effort fails in future. Ideally, such measures would only be used as a temporary solution to buy us more time to implement proper emissions reductions to return Earth to a more sustainable footing.

Given the global impacts of such geoengineering projects, comprehensive studies involving multiple countries, overseen by bodies like the United Nations, are imperative. Many uncertainties, from inaccuracies in dust deployment to potential damage to satellites, need thorough examination. While many oppose geoengineering as a foolhardy distraction from emissions reductions efforts, others counter that we should study these ideas lest we need them in a pinch.

In any case, the idea of using moon dust as a geoengineering solution underscores the urgency of our climate crisis. As tantalizing as the concept is, a lunar dust shield must be pursued with caution. We may be opening a proverbial Pandora’s Box: once we start, we may find ourselves locked into a solution that we have to maintain at any cost, whether we like it or not.

![could-moon-dust-help-reduce-global-temperatures?-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/146499-could-moon-dust-help-reduce-global-temperatures-hackaday-scaled.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)