Books You Should Read: Prototype Nation [Hackaday]

Over the years, I’ve been curious to dig deeper into the world of the manufacturing in China. But what I’ve found is that Western anecdotes often felt surface-level, distanced, literally and figuratively from the people living there. Like many hackers in the west, the allure of low-volume custom PCBs and mechanical prototypes has me enchanted. But the appeal of these places for their low costs and quick turnarounds makes me wonder: how is this possible? So I’m left wondering: who are the people and the forces at play that, combined, make the gears turn?

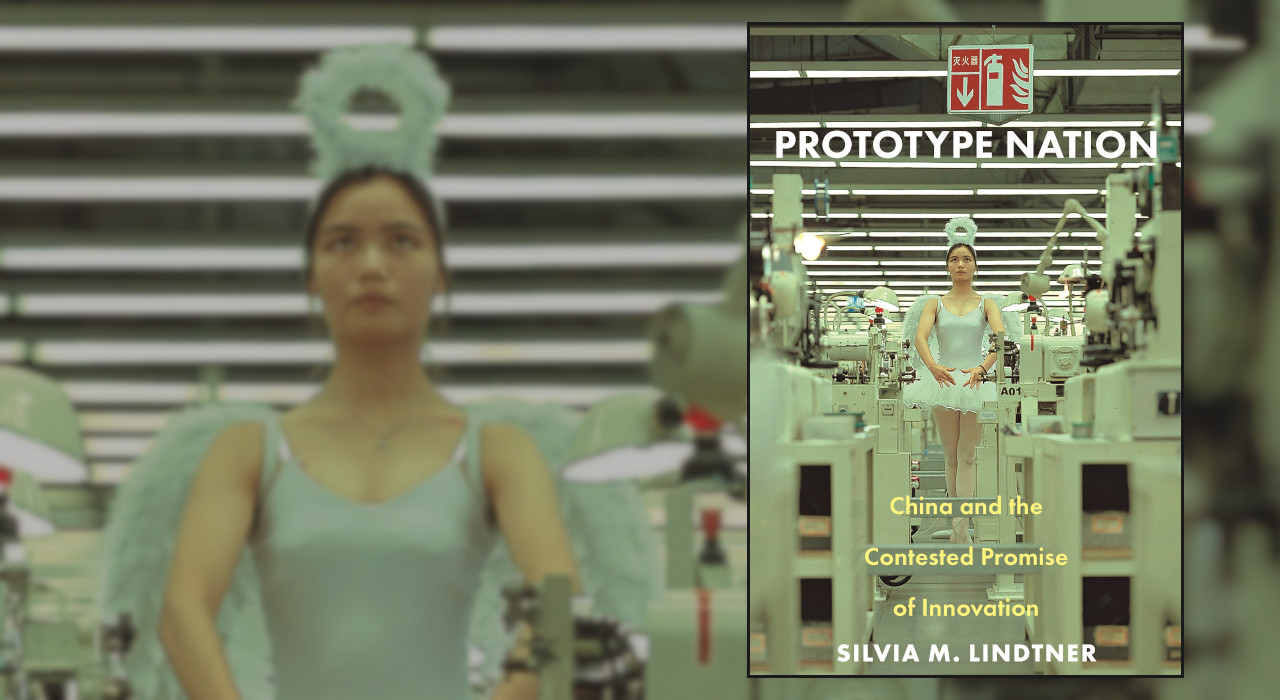

Enter Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation, by Silvia Lindtner. Published in 2020, this book is the hallmark of ten years of research, five of which the author spent in Shenzhen recording field notes, conducting interviews, and participating in the startup and prototyping scene that the city offers.

This book digs deep into the forces at play, unraveling threads between politics, culture, and ripe circumstances to position China as a rising figure in global manufacturing. This book is a must-read for the manufacturing history we just lived through in the last decade and the intermingling relationship of the maker movement between the west and east.

From Copy to Prototype

Lindtner does a spectacular job detailing why Chinese manufacturers will readily duplicate and resell existing designs. The answer is multi-faceted but involves, in part, a culturally distinct approach to designs. Duplication offers a means of reverse engineering, a way of understanding how something works. In fact, a number of designs known as gongban (pg 94) regularly circulate openly across factories as templates. The consequence is not only the means of manufacturing something akin to the original, but a way of producing original designs too via customizations that can freely run wild. Lindtner’s punchline in all of this is that the copy is essentially the prototype.

Of course, bootstrapping manufacturing pipelines for existing products does have the consequence of building a Western perception of Chinese manufacturing as a sort of copycat. Lindtner engages with this idea as well, noting how some Western maker labels devote extra work to qualify their means of production in China as genuine (think Arduino “Genuino”) while others emerging directly from China like Seeed Studio have had to push through this perception to break into Western markets.

With gongban, manufacturing in China has developed under circumstances where unlicensed sharing is the norm. In a way, this culturally distinct approach challenges the Western style of binding designs to terms set by the creator. It’s almost as if the west were to operate with permissive open source licenses being the default, and it begs the question: what kinds of innovation we would see if this kind of relationship to designs existed in the west?

The Politics at Play

None of this manufacturing growth has happened in a vacuum. It turns out that a collection of forces loosely motivate this sort of rapid manufacturing development in China.

First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has somewhat adopted the promise of the maker movement and used it, in part, to spur economic growth by creating a strong connection between making and entrepreneurship. Here, starting off as maker puts you on a path towards happiness by ultimately starting your own business. It’s no coincidence that the west now regularly sees Shenzhen as the “Silicon Valley of Hardware.” Both careful branding and financial investments via recognizing Shenzhen as a “Special Economic Zone” have made this the case.

On the other hand, the capacity to manufacture electronics cheaply has also brought in business from the west. Lindtner notes a number of Western articles comparing manufacturing in China as “going back in time,” and she ties this frontier-like perception to other scholarship that digs into the aftermath of Western colonialism. Overall, the politics between west and east are vastly complicated, and this section of the book makes for an eye-opening read.

And Much More

This article is only teasing you with a few highlights. Fret not, Dear Reader, with just over 220 pages and a thick bibliography to sink your teeth into, there’s plenty left to walk through. If you’ve ever been curious to step into the world of manufacturing in China, this book is a must-read. Give yourself a few afternoons, and let the details of prototyping in China draw you in.

![books-you-should-read:-prototype-nation-[hackaday]](https://i0.wp.com/upmytech.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/127063-books-you-should-read-prototype-nation-hackaday.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)